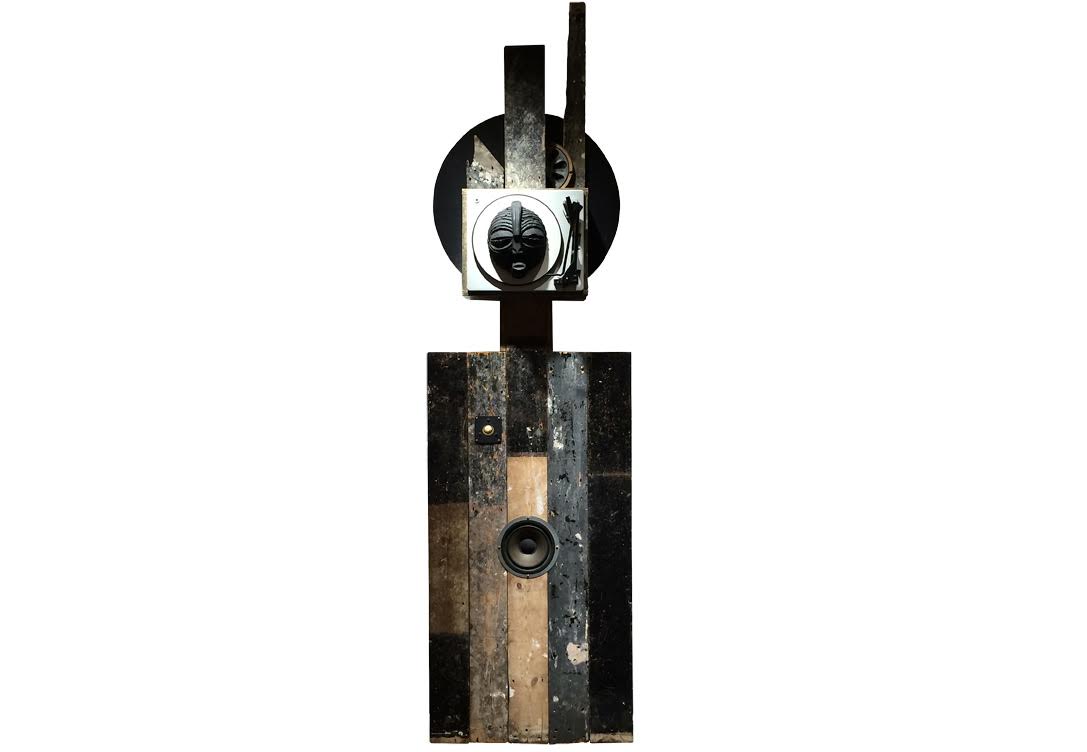

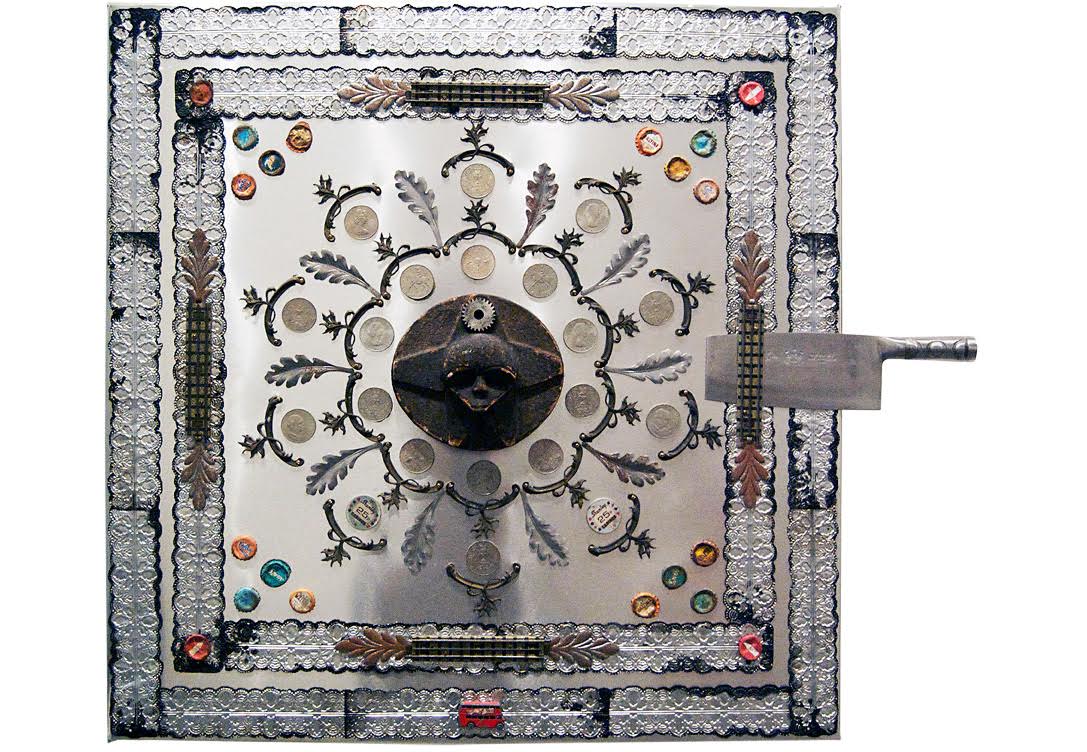

The Invisible Men is a series of sculptural works by British artist, Zak Ové.

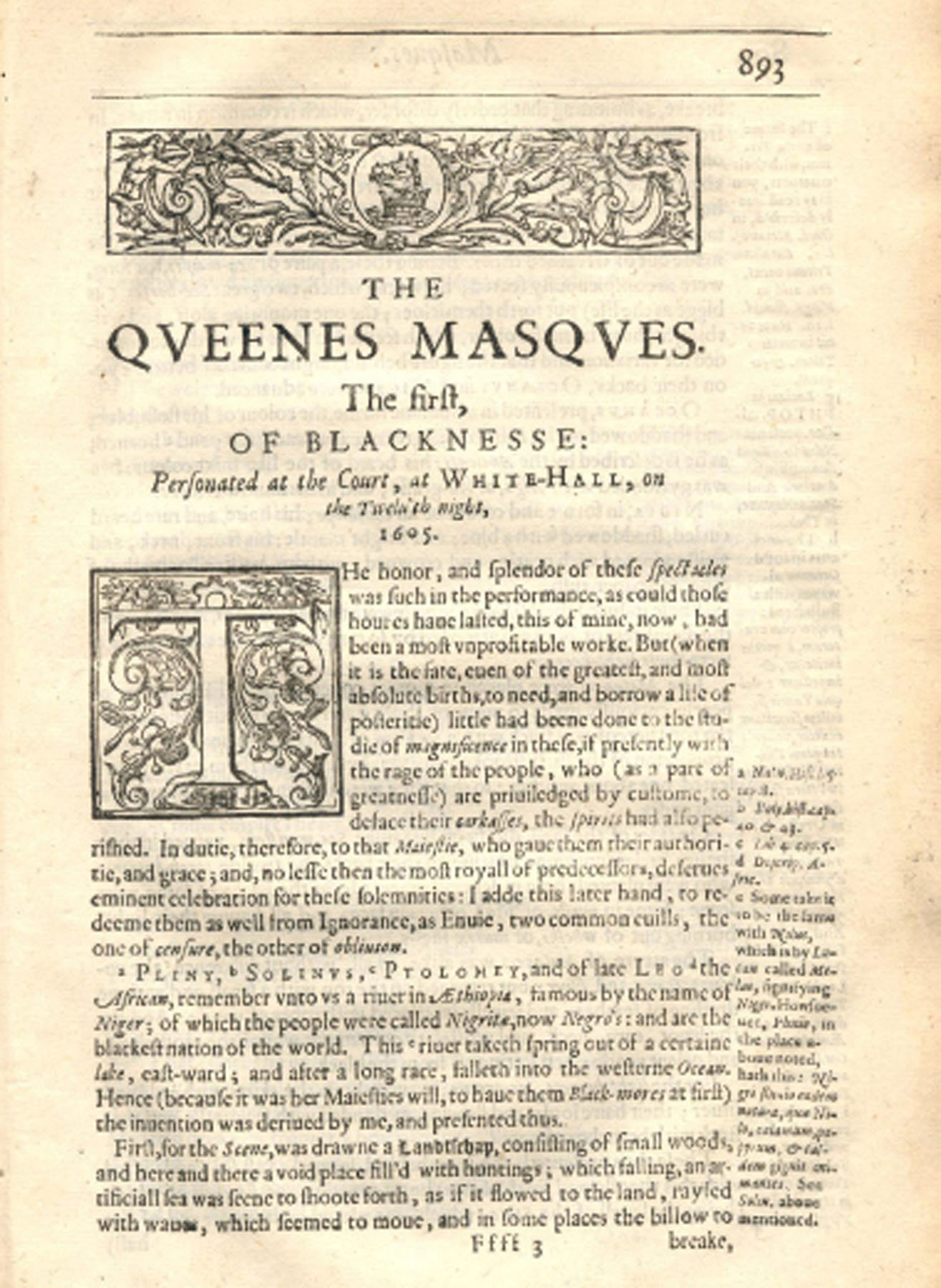

The series’ first iteration came in the form of a monumental sculptural installation, commissioned by Modern Forms for the courtyard of Somerset House for 1.54 Contemporary African Art Fair in October, 2016. It was conceived as a celebratory act of cultural revisionism, in part a contemporary riposte to Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Blackness. Commissioned by Anne of Denmark, James I’s wife, who once lived at Somerset House, the masque is one of the first representations of blackness in English drama and follows the quest of a number of Ethiopian water nymphs to lighten the colour of their skin in the pursuit of perfect beauty.

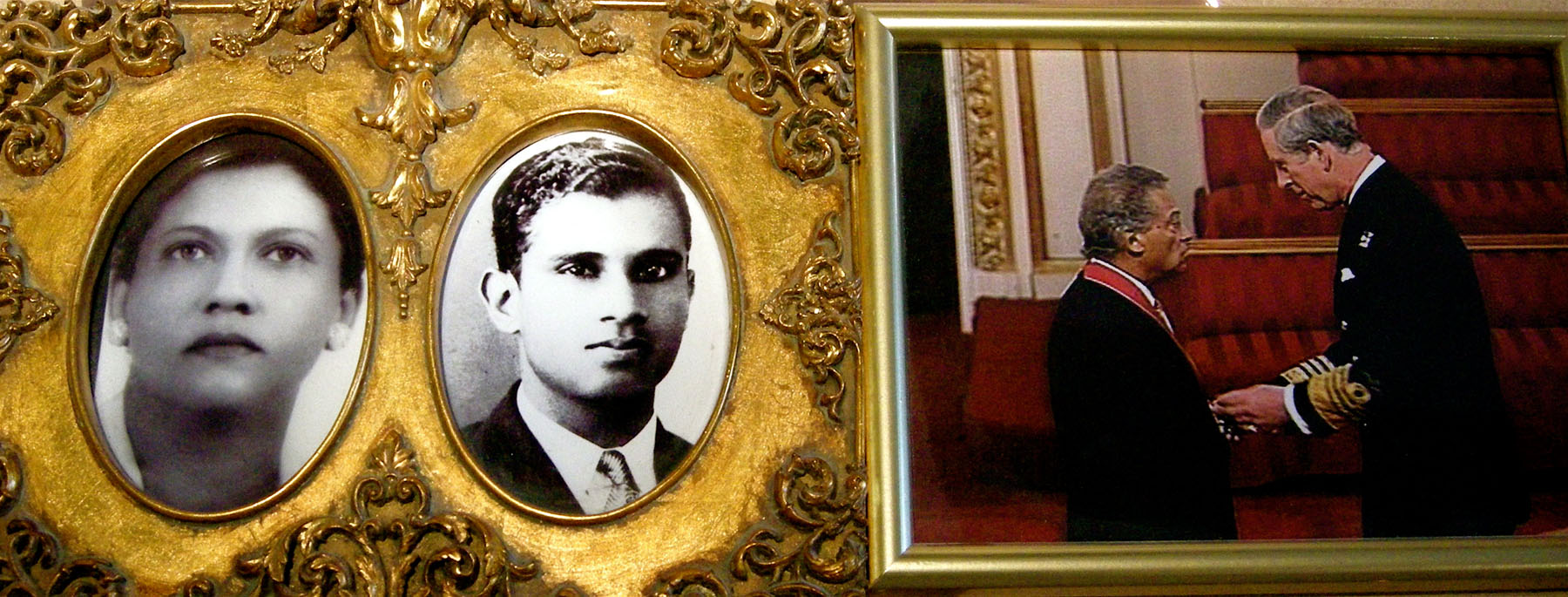

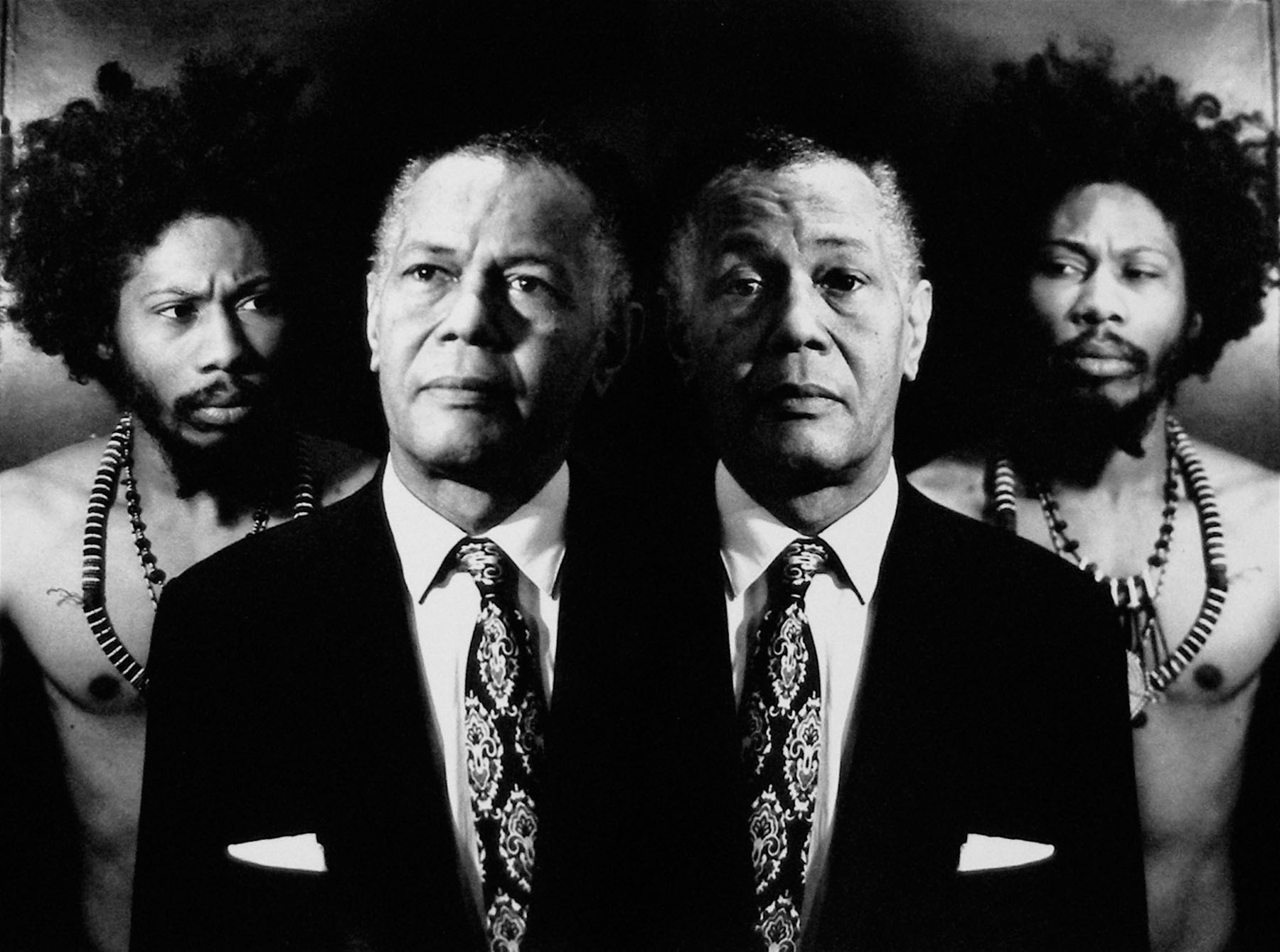

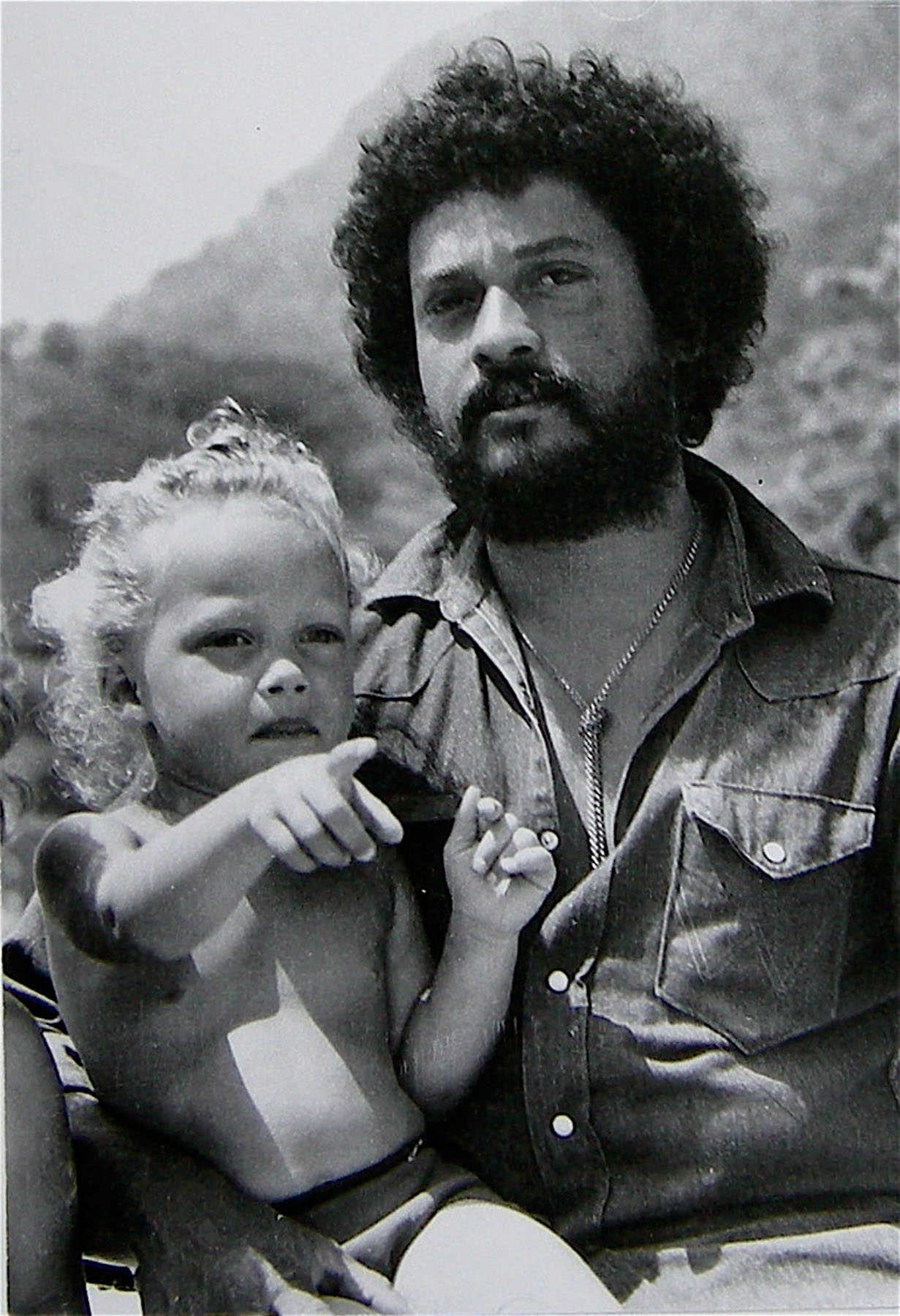

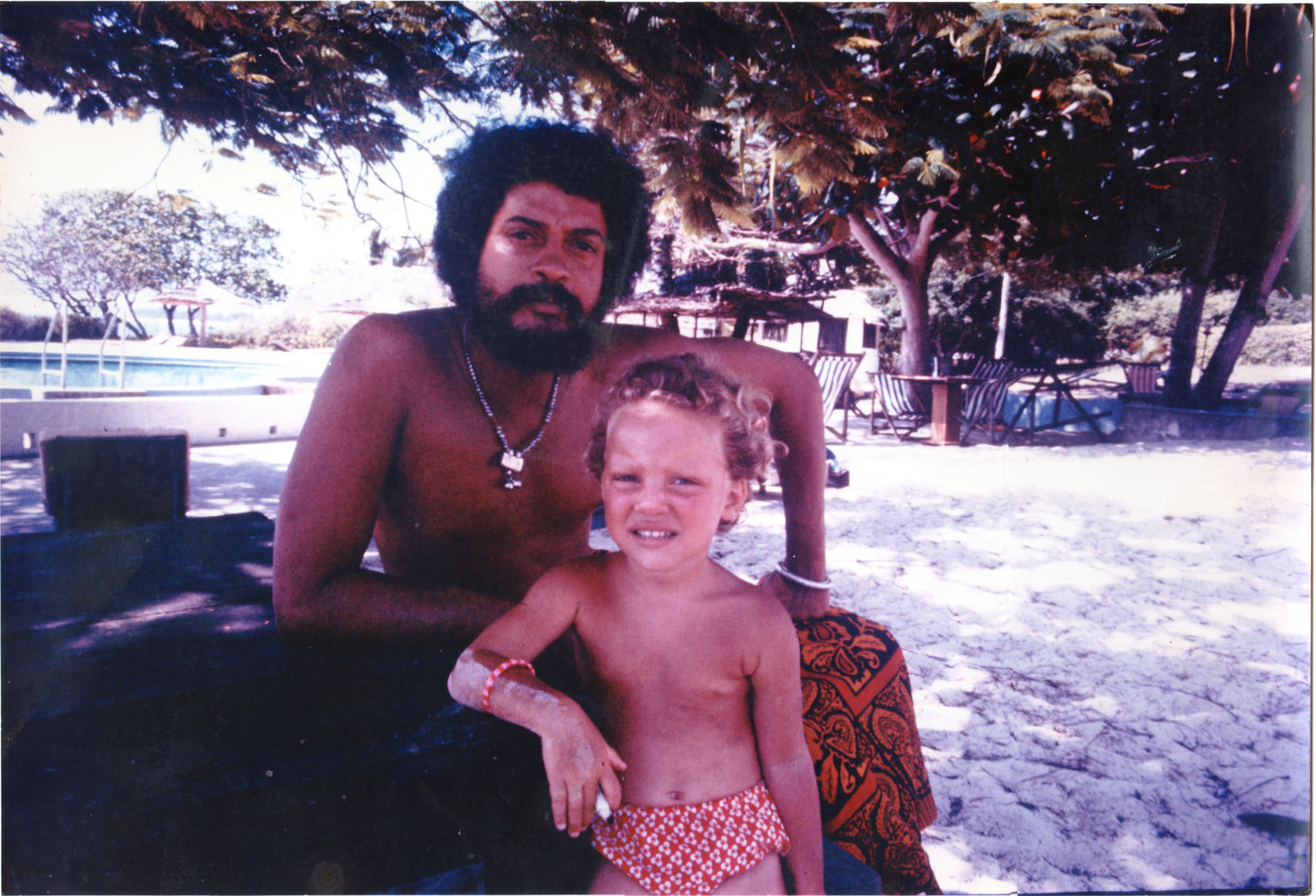

At Somerset House, The Invisible Men comprised of forty, 7ft sculptures, the repeated figure rescaled from an ebony wood African sculpture, given to Zak in the 70’s by his father, renowned film maker Horace Ové. The sculpture depicts a powerful male figure with both hands raised in an act of peace.

The Invisible Men emerges from a rich personal, cultural and historical context, encompassing: Jonson’s The Masque of Blackness, the work of Horace Ové, Ralph Ellison’s seminal novel The Invisible Man and the radical, emancipatory potential of the culture of Carnival.

Modern Forms worked with Ové to create the following online archive to partially articulate these strands of history and culture.

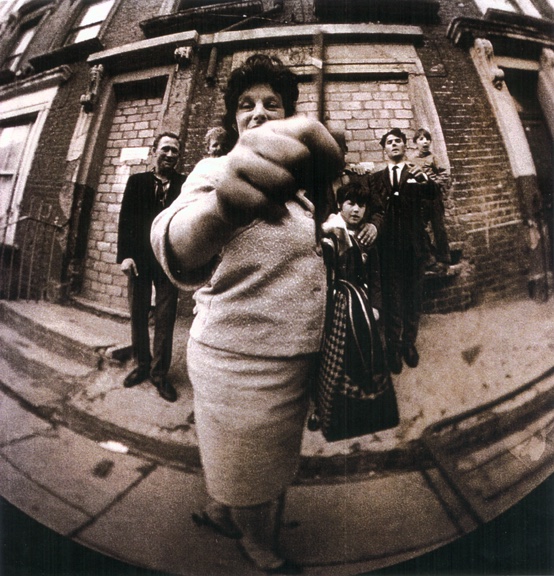

Horace Ové

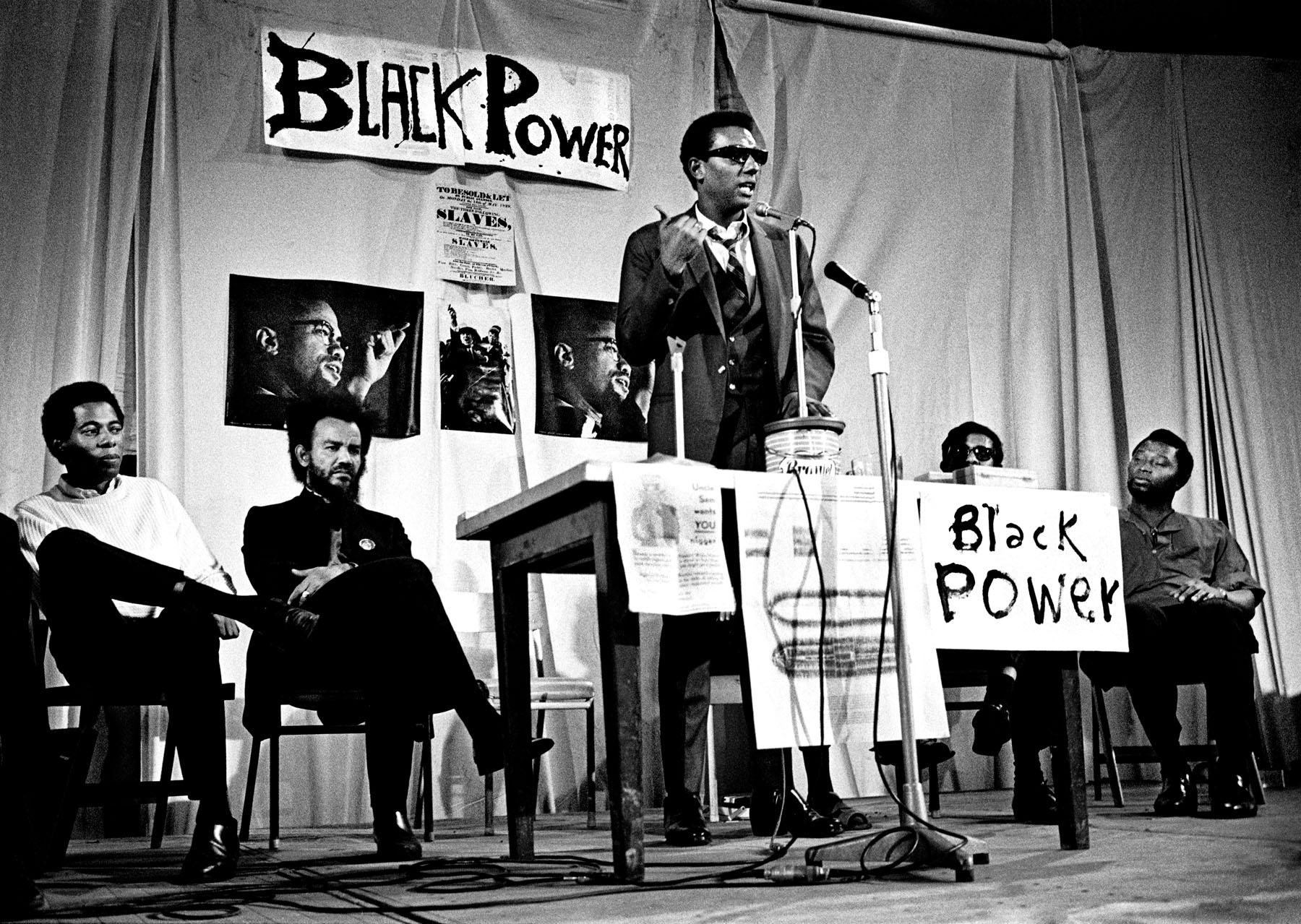

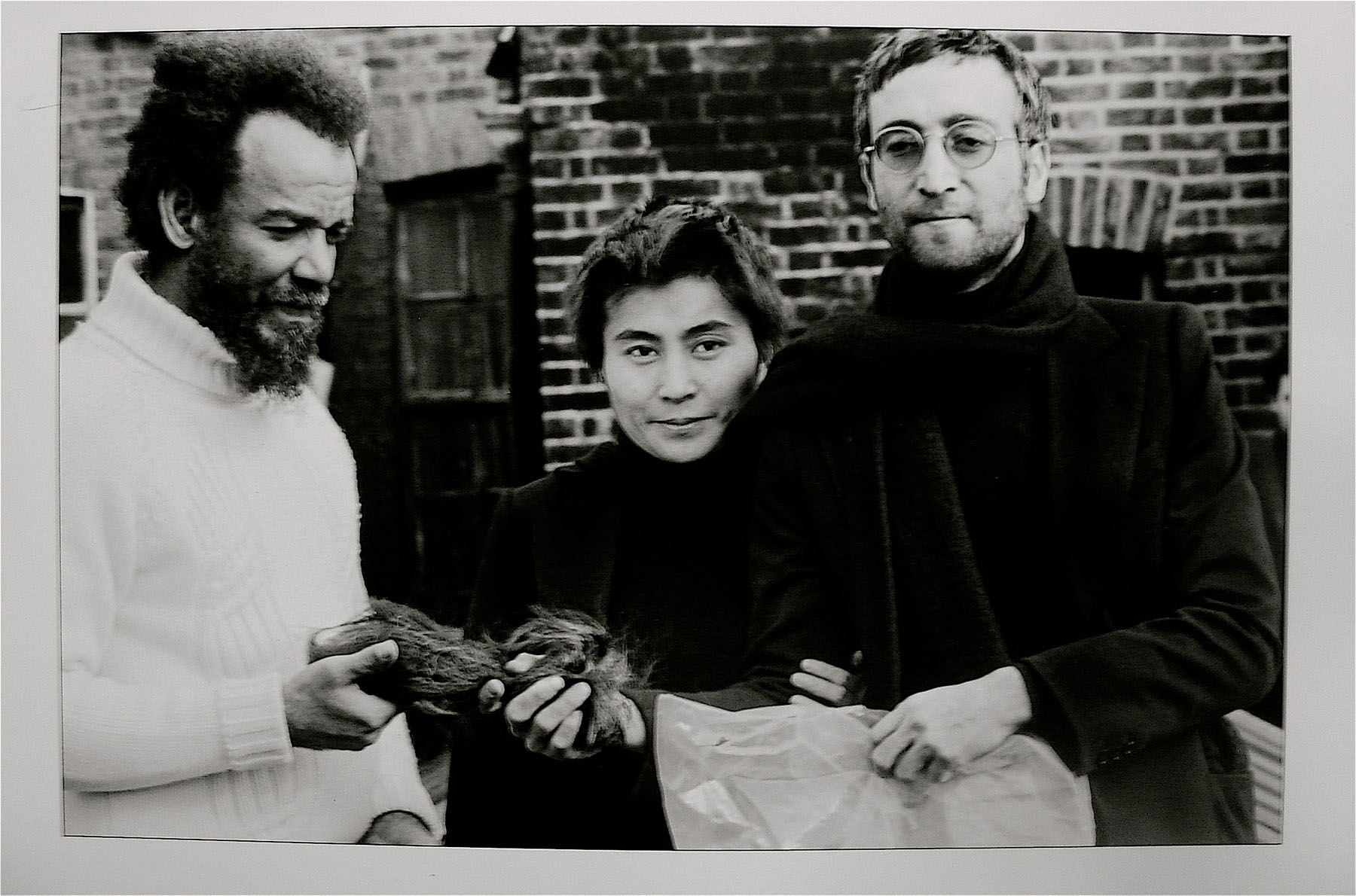

Horace Ové was born in Belmont, Trinidad and Tobago, in 1939. He came to Britain in 1960 to study painting, photography and interior design. After working as a film extra in Rome, he returned to London to study at the London School of Film Technique. He began work on Man Out, a surreal film about a West Indian novelist who has a mental breakdown. The project was never completed, but in 1966 Ové directed The Art of the Needle, a short film for the Acupuncture Association. This was followed by another short, Baldwin’s Nigger (1969), in which novelist James Baldwin discusses Black experience and identity in Britain and America.

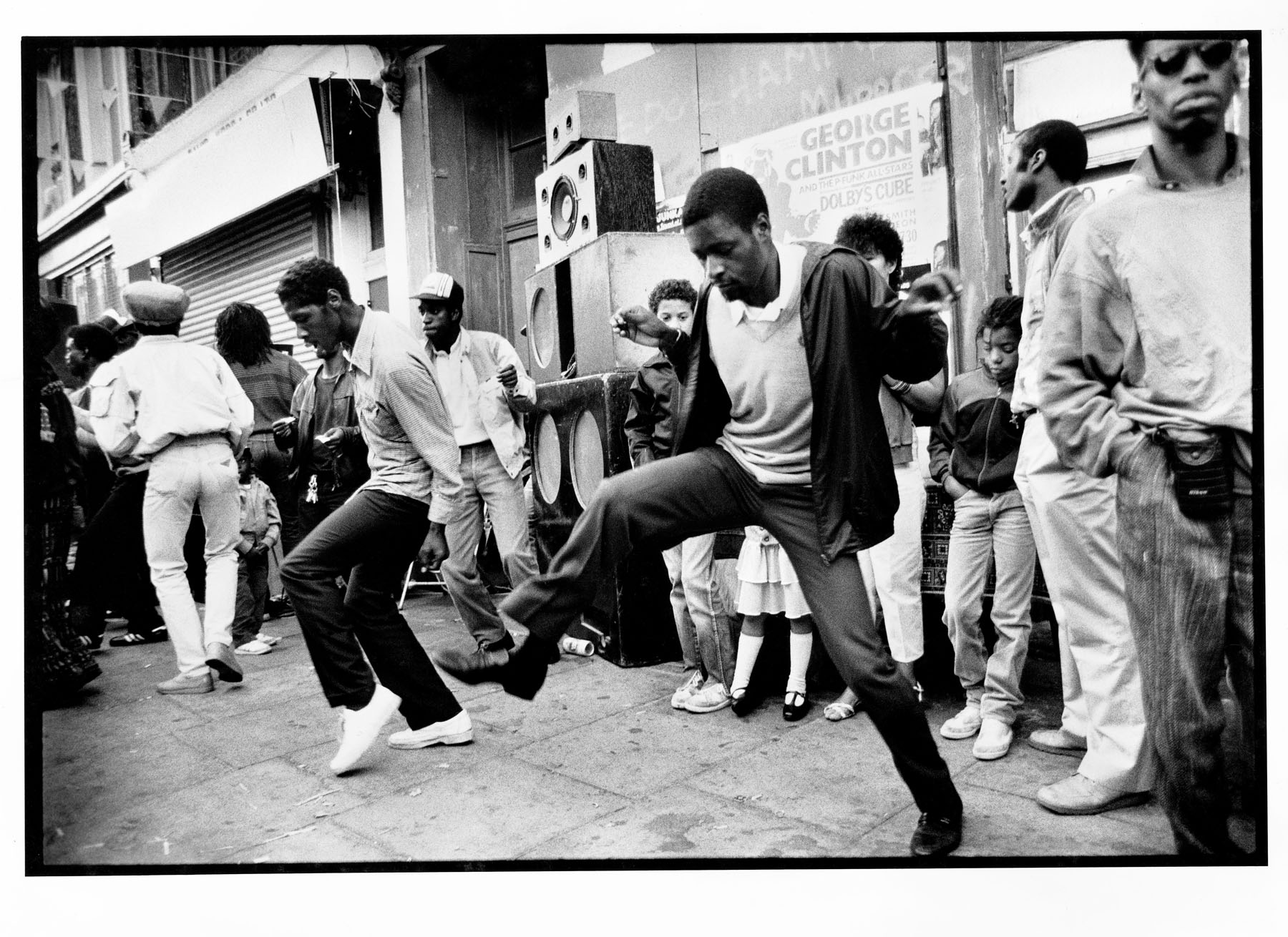

Ové’s next film, Reggae (1970), was a documentary examining what was then an underground music genre. It was the first feature-length film financed by Black people in Britain (funded by Junior Lincoln, a record producer), and was successful in cinemas and was shown by the BBC.

Reggae‘s success helped open some hitherto closed doors for Ové. Films made for the BBC’s World About Us series, such as King Carnival (tx. 22/7/1973) and Skateboard Kings (tx. 10/9/1978), showed Ové’s interest in representing multi- and sub-cultural lifestyles. Similarly, work for Channel 4, such as Music Fusion (17/7/1985) and Street Art (tx. 12/5/1984) documented the hybridity and vitality of Black British life. Playing Away (1986), a feature film made for Channel 4, told the fictional story of a West Indian cricket team from Brixton, playing against a village team as part of the village’s ‘Third World Week’ celebrations. The film demonstrates Ové’s ability to balance comedy with more serious issues, skilfully bringing out the race and class tensions underlying the cricket match.

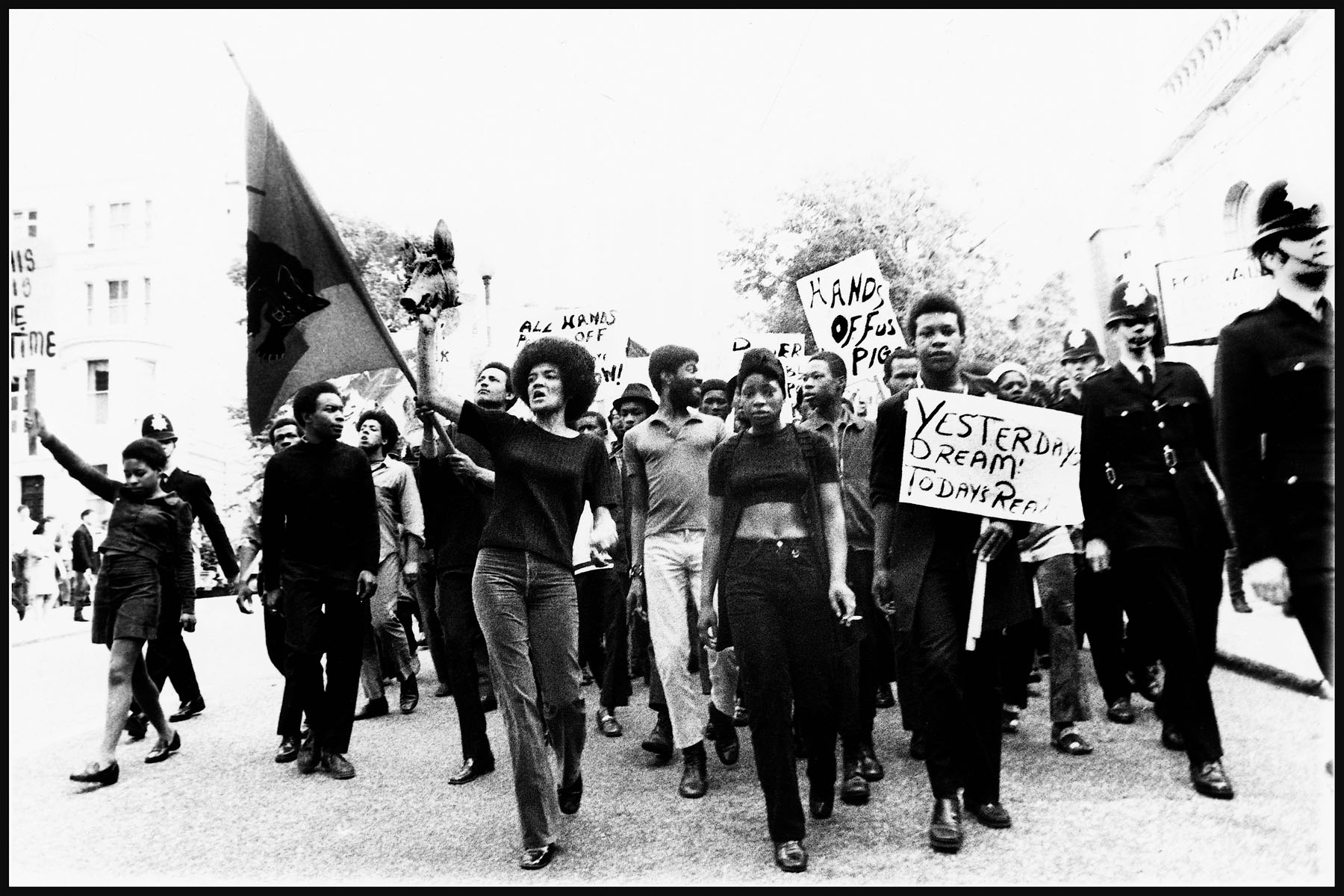

Ové has often looked to combine the form and style of documentary with more conventional drama. His most famous film Pressure (1975) – the first feature-length fiction film by a Black director in Britain – and A Hole in Babylon, made as a BBC Play for Today (tx. 29/11/1979) explore the problems facing young British Blacks, using the conventions of drama-documentary with gritty, naturalistic performances.

Both films caused controversy: Pressure was shelved for almost three years by its funders, the BFI, ostensibly because it contained scenes showing police brutality; A Hole in Babylon, an account of the 1975 Spaghetti House siege, was criticised for its sympathetic portrayal of the main characters, who were vilified in the press as a “bunch of black hooligans”. As Ové says, he wanted to show “that black people were fighting for their rights under a very racist situation and… were finding ways and means of demonstrating their feelings”. His importance as a film-maker therefore lies not just in his being the “first” Black director to break into the mainstream of television, but also in the committed political voice he retained once he had got there.

Text from Paul Ward, Reference Guide to British and Irish Film Directors.

Films

Links

Biography and filmography of Horace Ové on BFI : Screenonline

Horace Ové: Coming Home. Polly Pattullo, Carribean Beat, Issue 10, Summer 1994

Horace Ové, My Best Shot, The Guardian, August 25, 2016

Images

Zak Ové

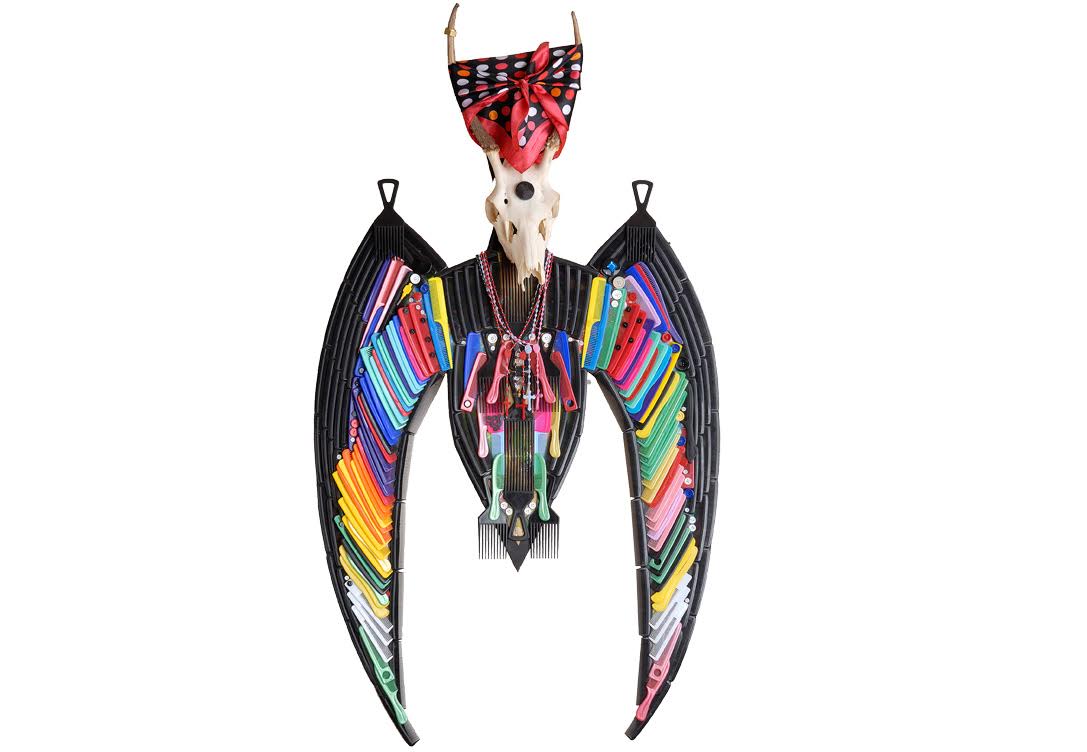

In his powerful photographs, films, paintings, and sculptures, Zak Ové mines his own Trinidadian and Irish heritage, which he describes as “black power on one side and… social feminism on the other side.”

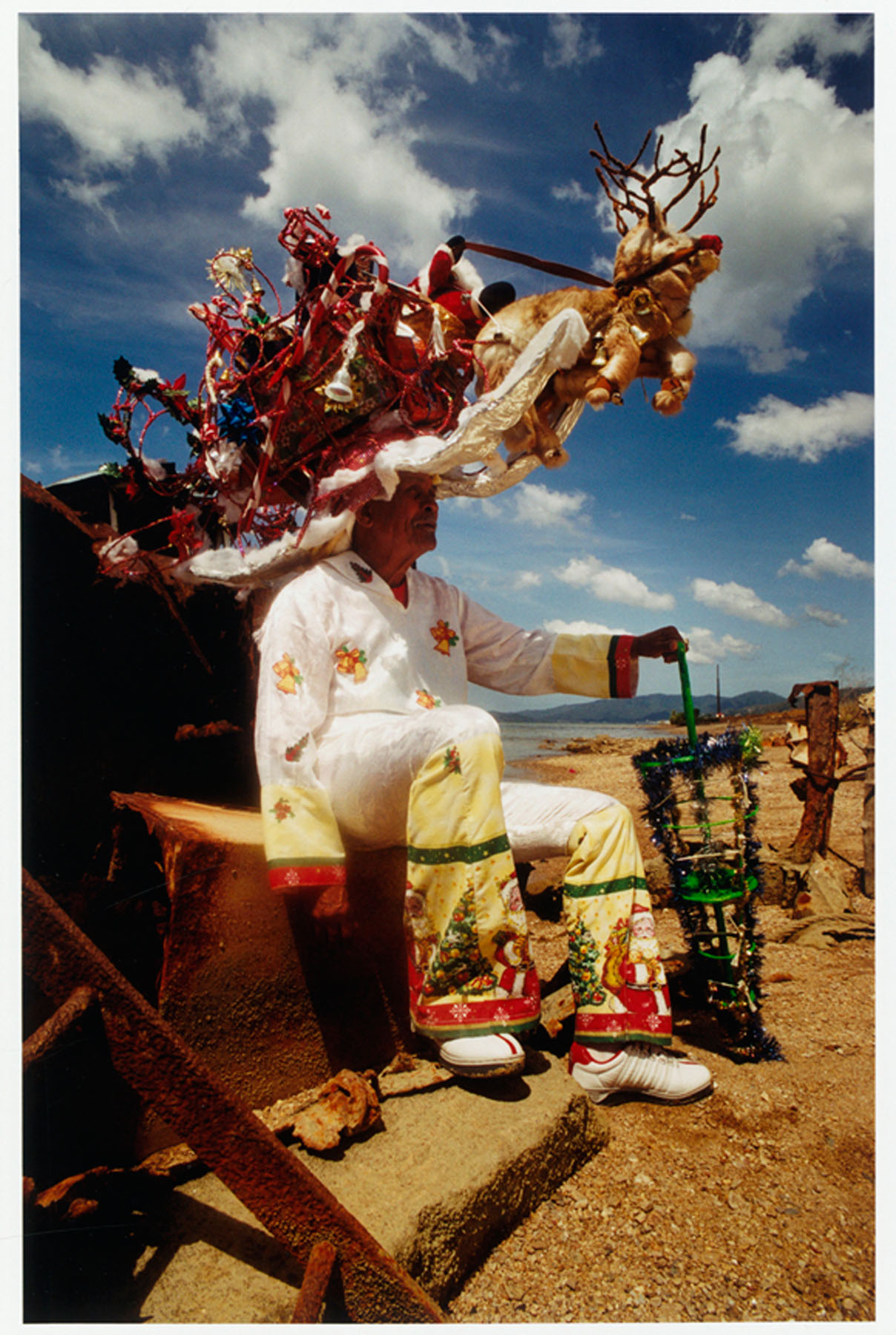

His work delves into post-colonialism in Britain and Trinidad, the African Diaspora, contemporary multiculturalism, globalization, and the blend of politics, tradition, race, and history that informs our identities. Influenced by the pioneering films of his father, Horace Ové, Zak Ové began his artistic career with a series of exuberant photographs of the participants in Trinidad’s vibrant, multivalent Carnival. He later made forays into sculpture, which he approaches as a form of narrative. Through his sculptural figures, concocted from a dynamic assortment of materials, and resembling African and Trinidadian statuary, Ové plays with notions of identity, positing the self as complex, open, and interconnected.

Images

Films

Links

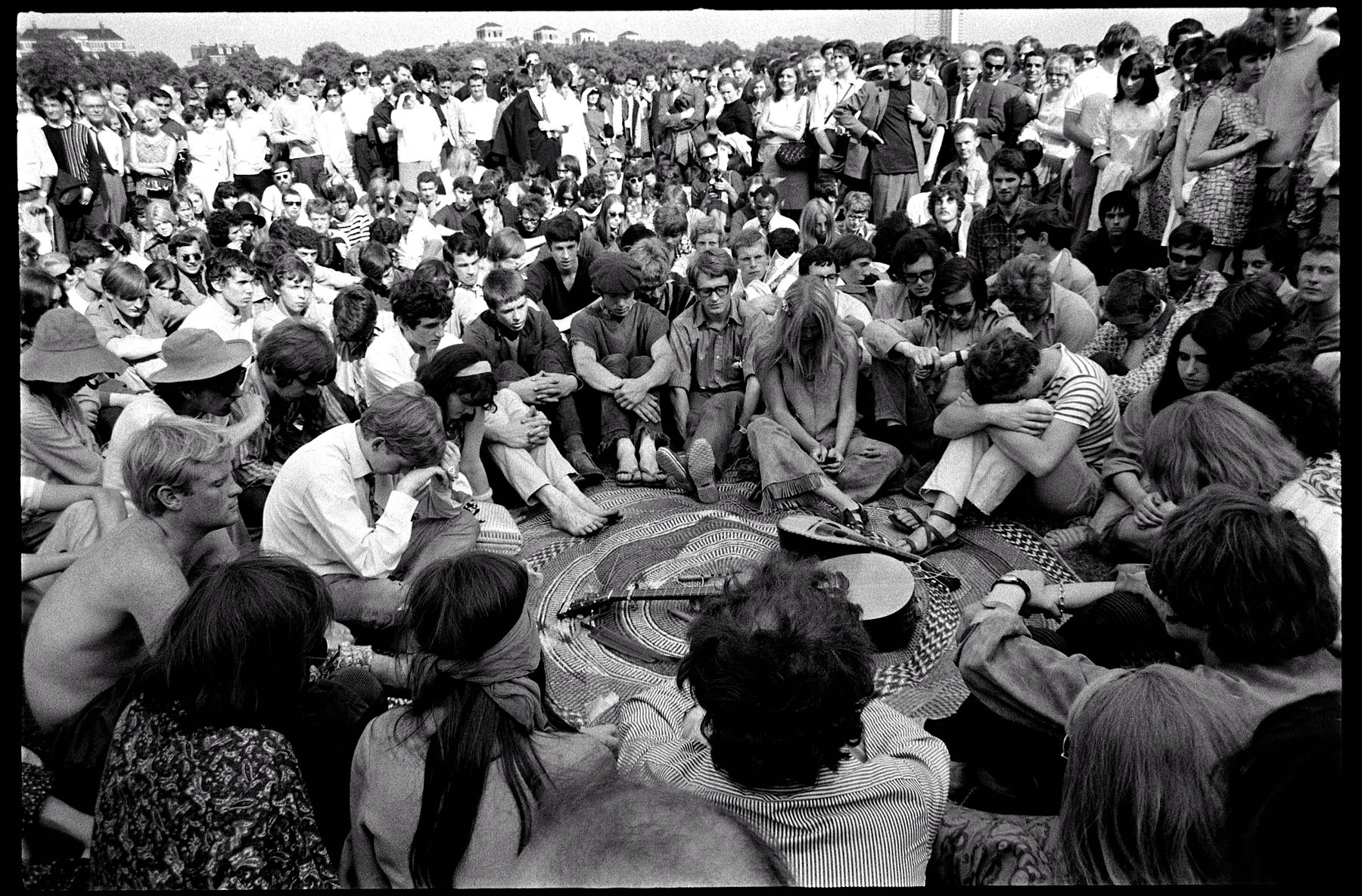

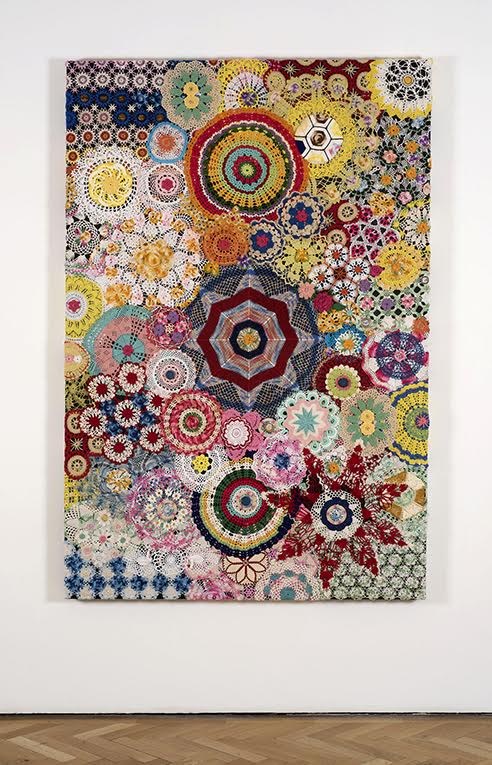

Carnival

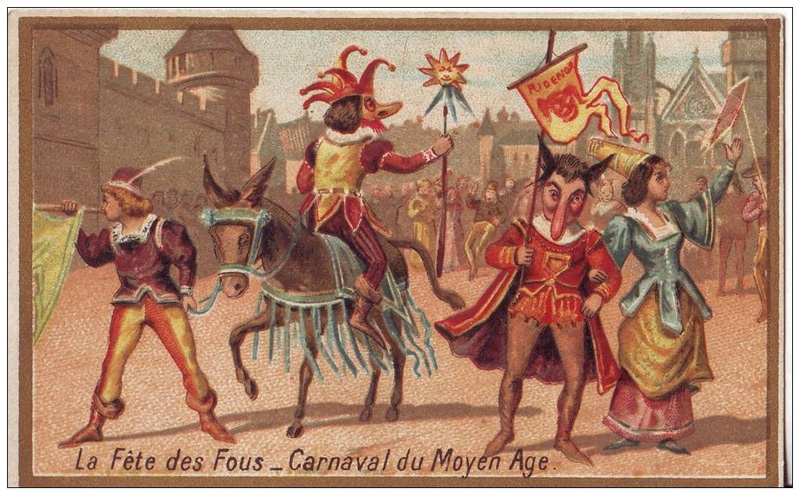

The essential form of the Carnival that emerged and developed in the post Classical West was created by the interaction of two diametrically opposed but interlocking forces – the desire of dominant power to contain potentially existentially threatening social energies through sublimation in the form of a regular (typically annual) reversal ritual in which the normally dominant hierarchy and ideology were theatrically mocked, subverted or ignored and social roles reversed – and conversely, the desire of the relatively powerless to express those very energies.

In much of Western Europe Carnival emerged as an ‘officially licensed’ – by the Catholic church and local temporal power – annual spring ritual involving feasting, and general play, that was held just before Lent. What was a thinly disguised pagan, fertility ritual, recast by the Church in attempt to co-opt its energies, also served temporal power through the ritualized dissipation of energies potentially threatening to the social order.

The form and tradition of carnival spread to the Caribbean and the Americas, brought by European colonialists. In all these territories the carnival tradition was instituted by local elites for the same systemic purposes of the regulation of disruptive energies. However the resistance and independence movements in many Caribbean countries developed out of carnival culture, where the annual theatricalized role reversal of social positions encouraged

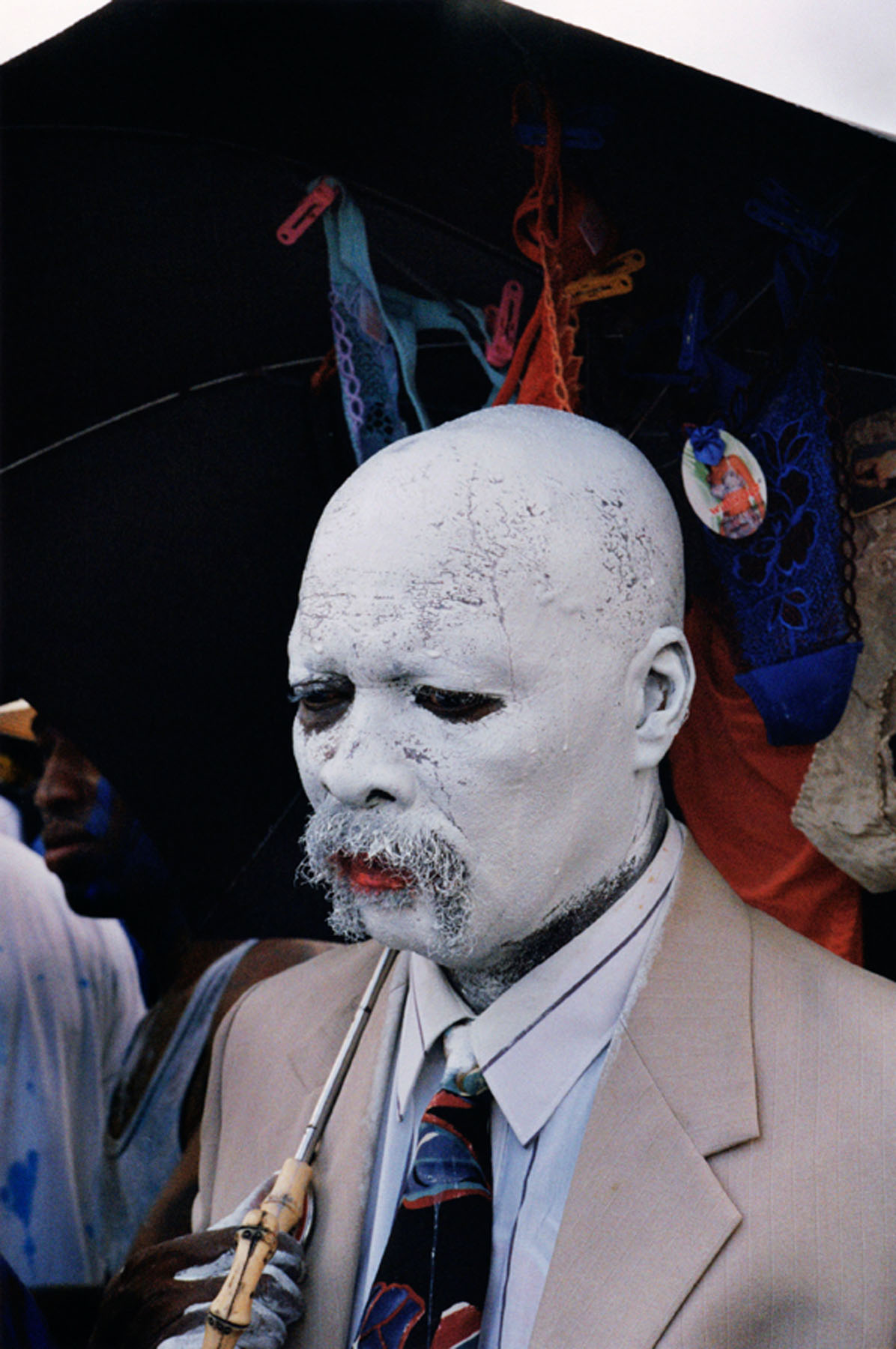

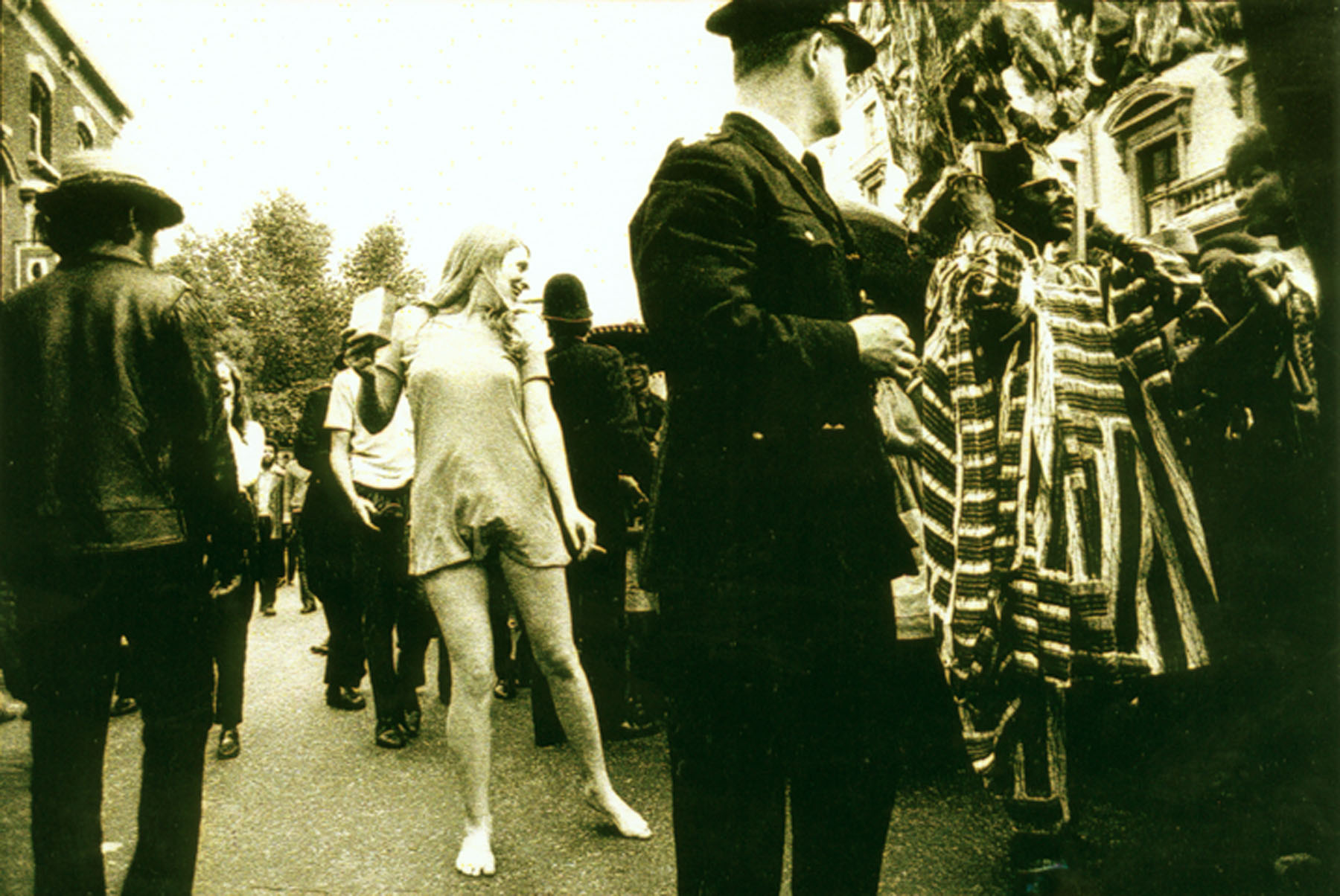

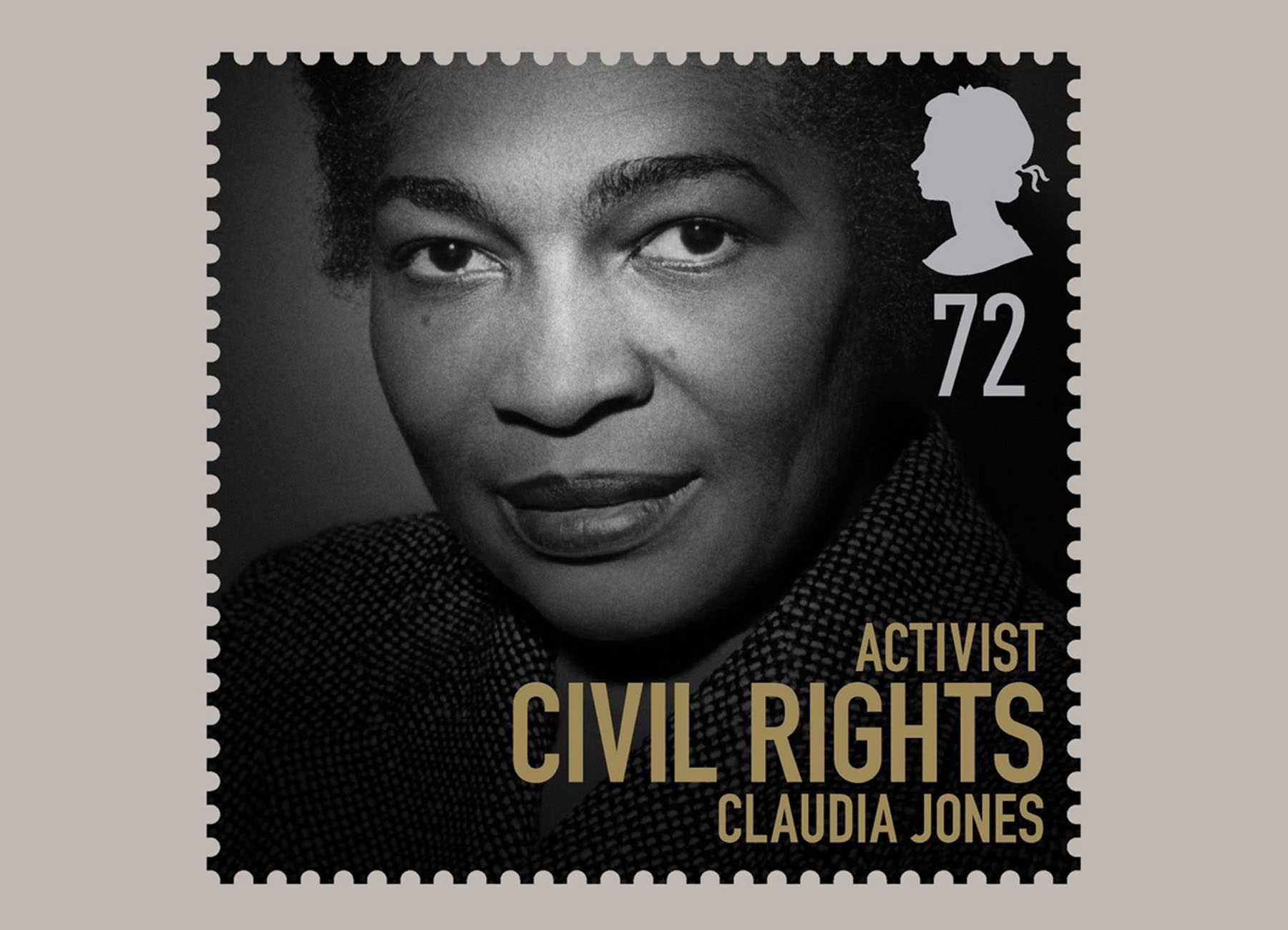

In England the Notting Hill Carnival developed after Trinidadian born activist Claudia Vera Jones, suggested the creation of an annual ritual along the lines of a Mari Gras festival, in London, after the race riots in Notting Hill of 1958. Here the expressive and hedonistic power of carnival was envisaged as a force for social cohesion and as an instrument of racial integration.

Videos

Zak Ové – Images of Carnival

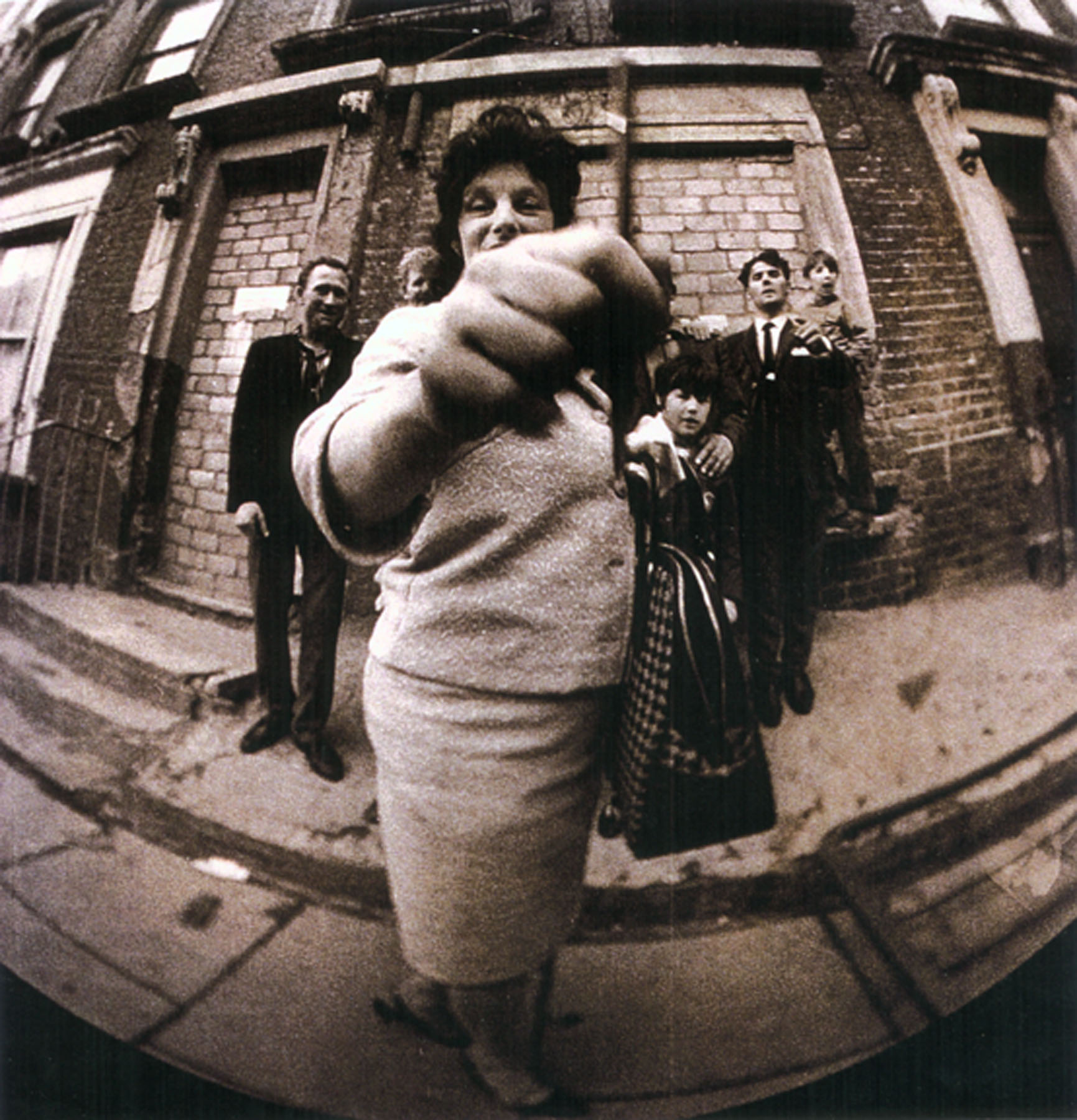

Horace Ové – Images of Carnival

Historical Images of Carnival

Links

Claudia Vera Jones, Biography, Starry Messanger

Notting Hill Carnival: the early years, The Guardian, Josy Forsdyke, 24 August 2014

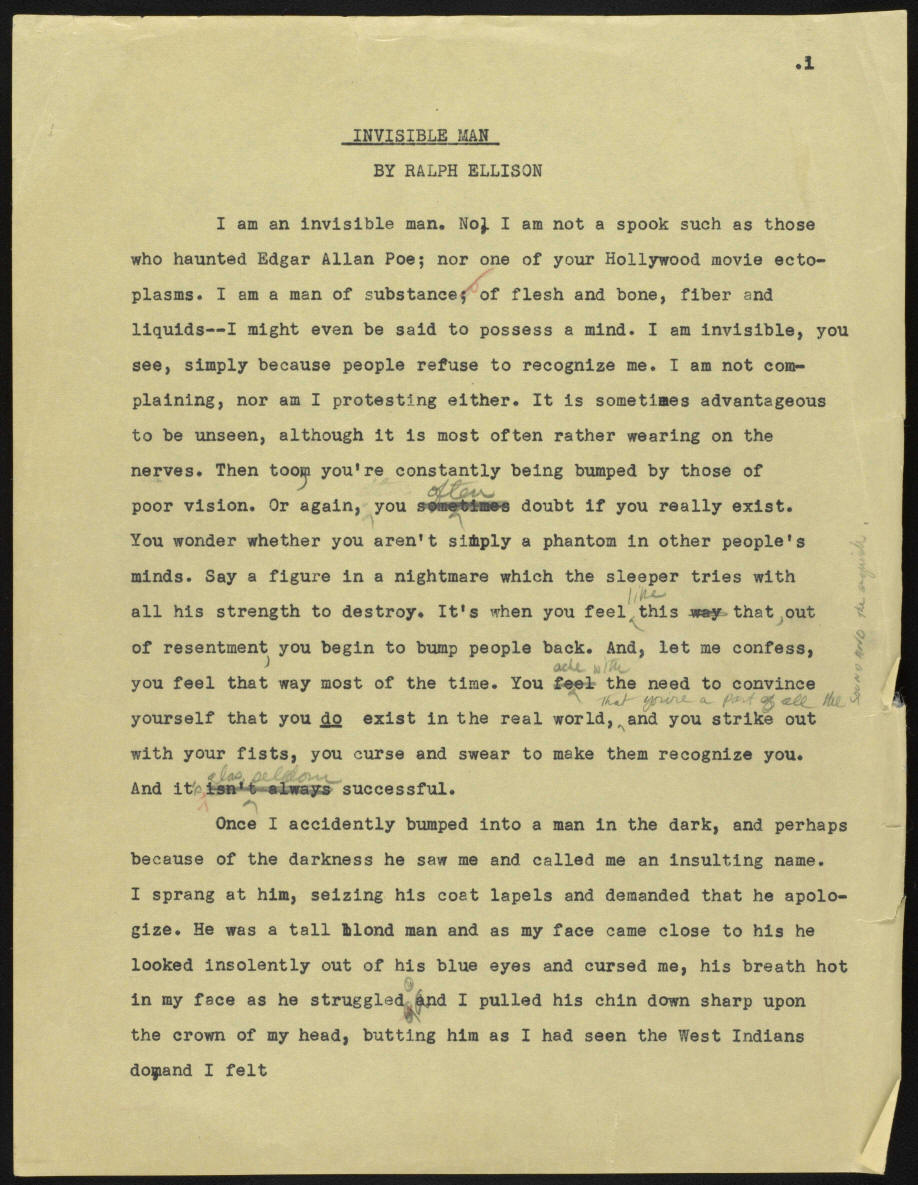

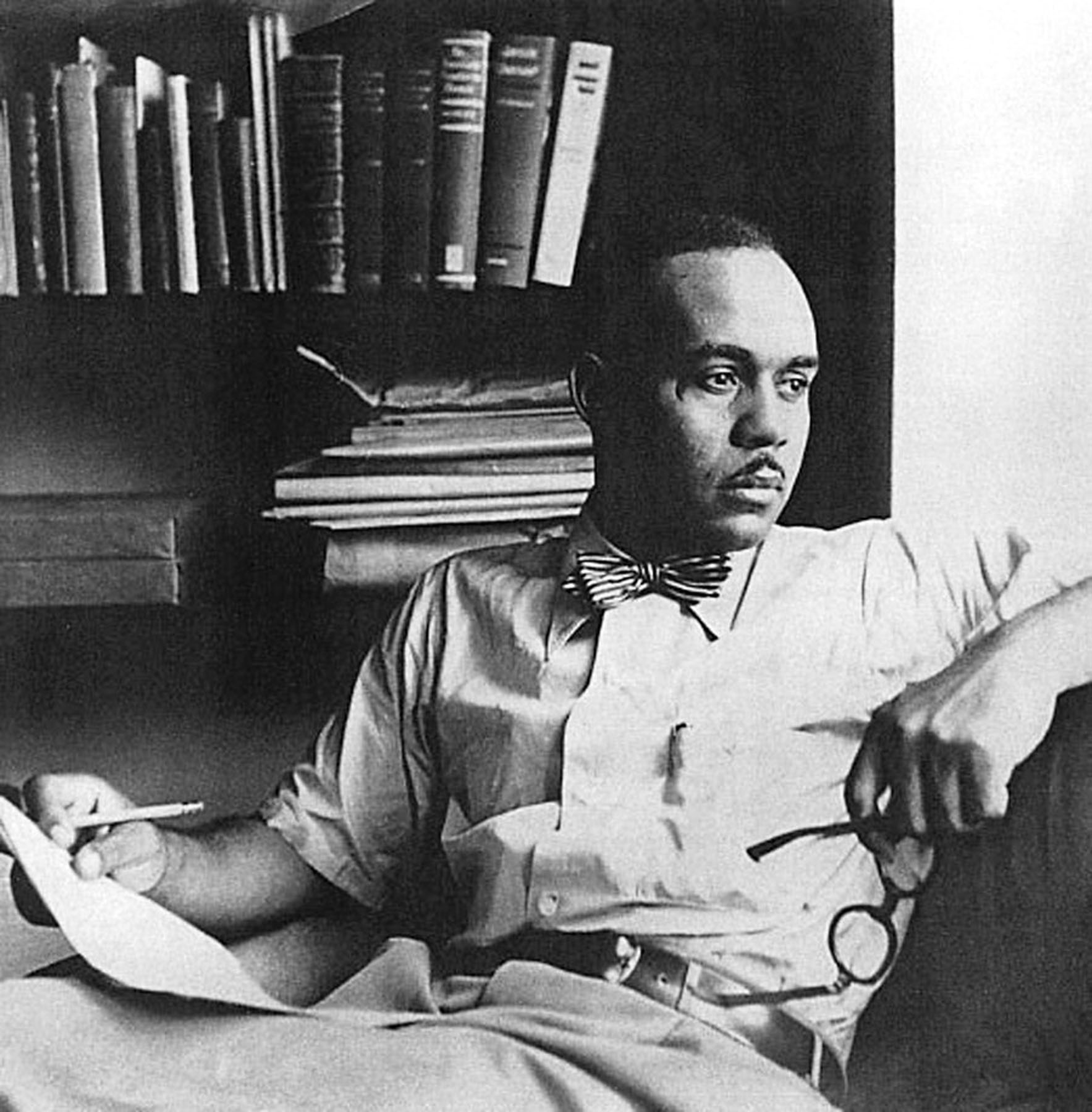

Ralph Ellison (1914 – 1994)

Born in 1914 in Oklahoma City, the grandson of slaves, Ralph Waldo Ellison and his younger brother were raised by their mother, whos husband died when Ralph was 3 years old. His mother supported her young family by working as a nursemaid, a janitor and a domestic.

From an early age Ellison loved music and expected to be a musician and a composer. He played his first instrument – a cornet – at age 8. By 19, he had enrolled at Tuskegee Institute as a music major, playing the trumpet. Although drawn to jazz and jazz musicians, Ellison studied classical music and the symphonic form because he was looking forward to a career as a composer and performer of classical music.

In the summer of 1936, Ellison went to New York City to earn expenses for his senior year at Tuskegee. It was a fateful decision: He never returned to his studies at Tuskegee and never became a professional musician. While in New York, Ellison met the writer Richard Wright. When they first became acquainted, Ellison had every intention of returning to Tuskegee. But the Great Depression prevented him from earning the needed funds.

Eventually he got a job doing research and writing for the New York Federal Writers Program, an offshoot of the Works Progress Administration. He also began writing essays and short stories for the “New Masses,” “The Negro Quarterly,” “The New Republic,” “Saturday Review” and other publications.

With the outbreak of World War II, Ellison joined the U.S. Merchant Marine as a cook, saw action in the North Atlantic and began to think of writing a major novel. However, not until after the war did he begin writing what was to become “Invisible Man.”

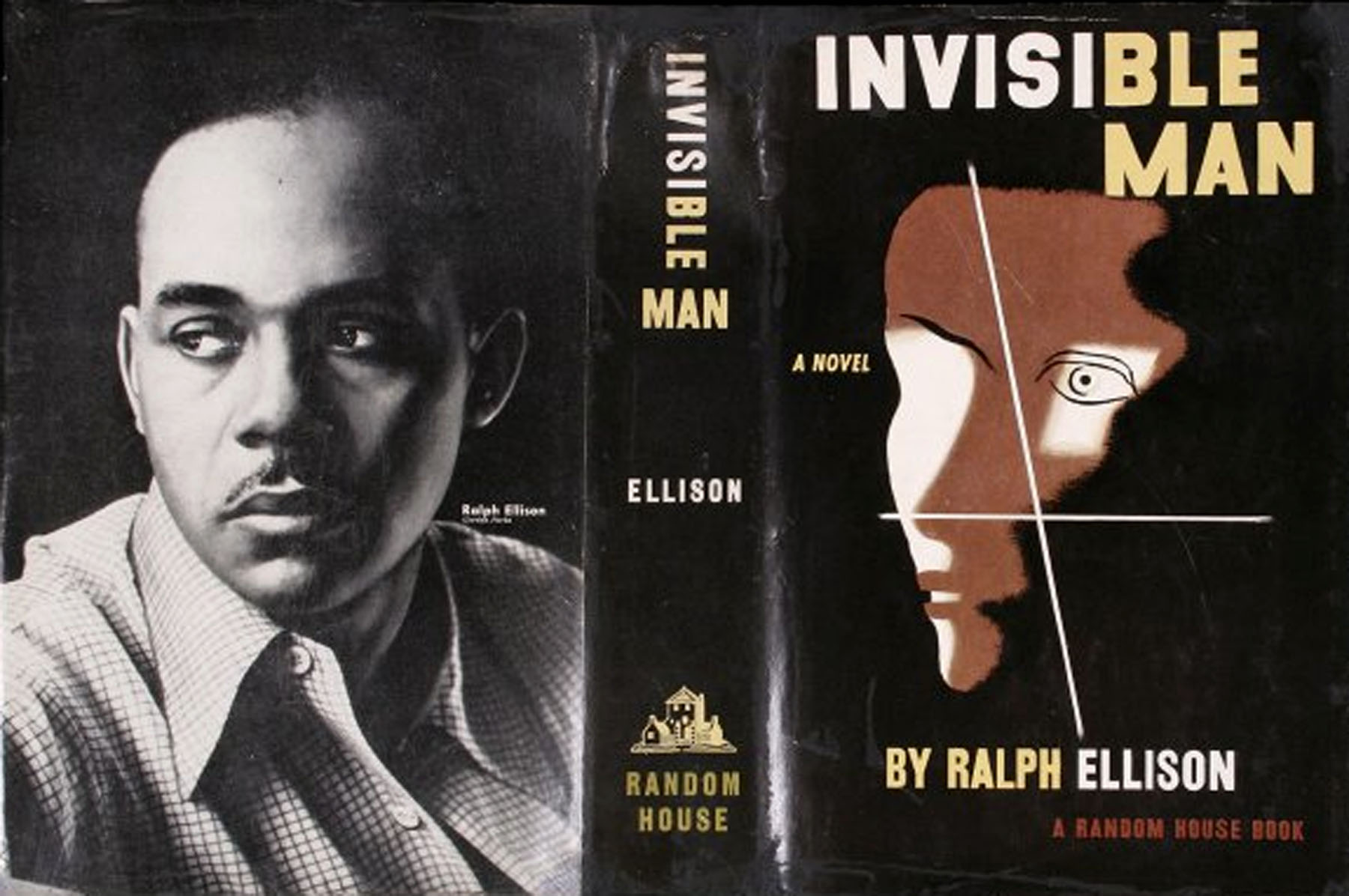

From the time Invisible Man first appeared in 1952, it was a popular and critical success. On the best-seller list for 16 weeks, in 1953 the novel won the National Book Award, beating John Steinbeck’s East of Eden and Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. And more than 40 years later, Nobel Prize winner Saul Bellow declared, “This book holds its own among the best novels of the century.”

“Invisible Man” established Ellison as a serious and important literary figure, and he spent the next two years (1955-57) in Rome as a Fellow of the American Academy. He returned to the United States to teach at a variety of colleges and universities including Bard College, the University of Chicago, Rutgers, Yale and New York University, among others.

He always maintained his wide range of interests – from music, both classical and jazz, to sports, theater and photography – and in 1964 he published “Shadow and Act,” a collection of essays on these and other subjects. Ellison has described the volume as an attempt “to relate myself to American life through literature.“Going to the Territory,” a subsequent collection of essays, lectures and criticism, appeared in 1986. For many years, Ellison worked on a second, long piece of fiction, which he never completed; it finally appeared after his death in 1994, as “Juneteenth.”

After a short-lived first marriage, Ellison married Fanny McConnell in 1946. A devoted couple, they lived together in an apartment on Riverside Drive in New York City until Ellison died in April 1994. There were no children. Fanny McConnell Ellison died in 2005 at the age of 93.

For many years, Ellison worked on a second, long piece of fiction, which he never completed; it finally appeared after his death in 1994 as “Juneteenth.”

A Selected Bibliography of the Work of Ralph Ellison

Invisible Man (1952)

Shadow and Act (1964)

Going to the Territory (1986)

Juneteenth (1999)

Awards

1953 National Book Award “Invisible Man”

1969 Medal of Freedom

1970 Chevalier de l’Ordre des Artes et Lettres

1985 National Medal of Arts

Texts

Justice for Ralph Ellison by David Denby, April 12, 2012 in The New Yorker

The Astrology of Ralph Ellison, Amir Bey, 2007

Films

Images

Ben Jonson & The Masque of Blackness

Benjamin “Ben” Jonson (1572 – 1637) was an English playwright, poet, actor, and literary critic of the 17th century, who had a lasting impact upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours. He is best known for the satirical plays Every Man in His Humour (1598), Volpone, or The Fox (c. 1606), The Alchemist (1610) and Bartholomew Fair (1614) and for his lyric poetry; he is generally regarded as the second most important English playwright during the reign of James I after William Shakespeare.

The Masque of Blackness was an early Jacobean era masque, first performed for the Stuart Court on Twelfth Night, 6 January 1605. Written by Jonson at the request of Anne of Denmark, the Queen consort of King James I, who wished herself and her court ladies, who were the main actors in the masque, to be disguised as Africans. Accordingly Anne and her court ladies performed in blackface makeup.

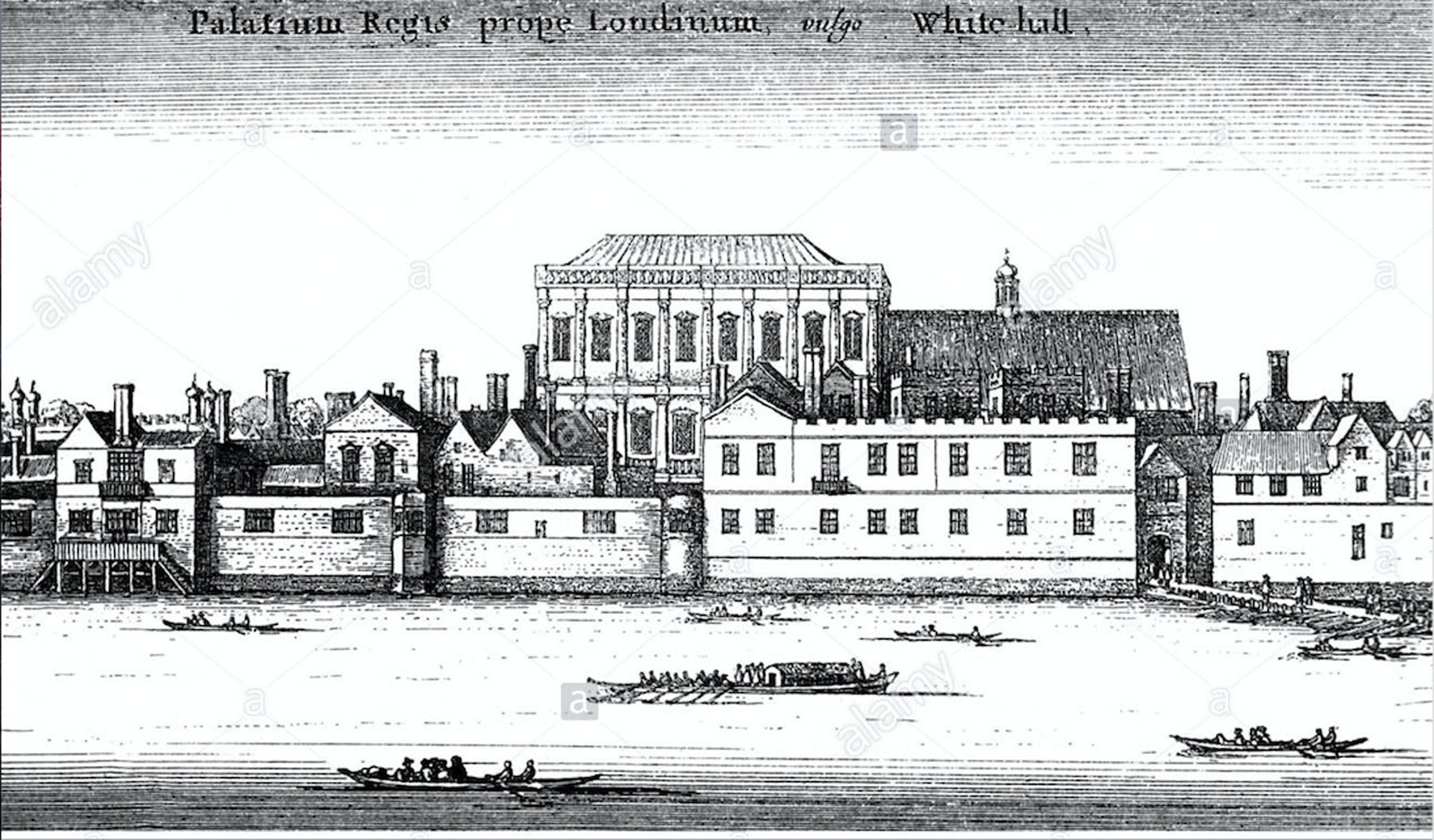

The Masque of Blackness was first performed in 1605 at the banquet hall of Whitehall Palace in London. Music begins, opening the stage to the water nymphs (or masquers), who were being played by Queen Anne and her ladies in waiting. They were dressed in blackface and costumes of blue, silver, and pearl to contrast with the ‘blackness’ of their skin.

The masque opens with a conversation between Oceanus (the god of the Atlantic Ocean) and Niger (the god of the Niger River). Oceanus asks Niger why he changed his river’s course and was now in the middle of the Atlantic. Niger explains that it was at the behest of his daughters, Ethiopian water nymphs.

His daughters, he explains, have recently been informed by the poets of the North that they are not as beautiful as they once thought they were. Despite being the first goddesses ever created, their blackness the epitome of African beauty created in the sun drenched deserts of Ethiopia, they now curse the sun that gave them life for making them too dark. He goes on to explain that the moon goddess, Aethipoia, appeared to the daughters to help them solve their dilemma, by informing them they needed to find a land which ended in -tania and there they would find their answer.

After traveling to all of the -tanias they knew of to no avail, Niger appeals to Aethiopia himself, asking her to explain what she means. The moon goddess appears on stage and tells Niger that the land his daughters seek is called Britannia, a land ruled by a sun-like king named James. If the daughters appear before him and his potent light of reason, the power of it will bleach away their blackness.