Phone interview between Peter Schuyff and Nick Hackworth on Sunday 29 March 2020. A show of Peter’s paintings from the 1980’s, curated by Katharine Kostyál, at White Cube, Masons’ Yard and a show of works on paper at Carl Kostyál both opened in mid-March. Both are currently suspended during the crisis.

Nick: So, how’s the apocalypse going for you?

Peter: Well, I’ve run out of pencil lead unfortunately. I’ve started work on this very obsessive project and I was using a rather specialised pencil and half-way through I ran out of lead and I can’t think of a single place where I might get more lead….

Nick: What’s the obsessive project?

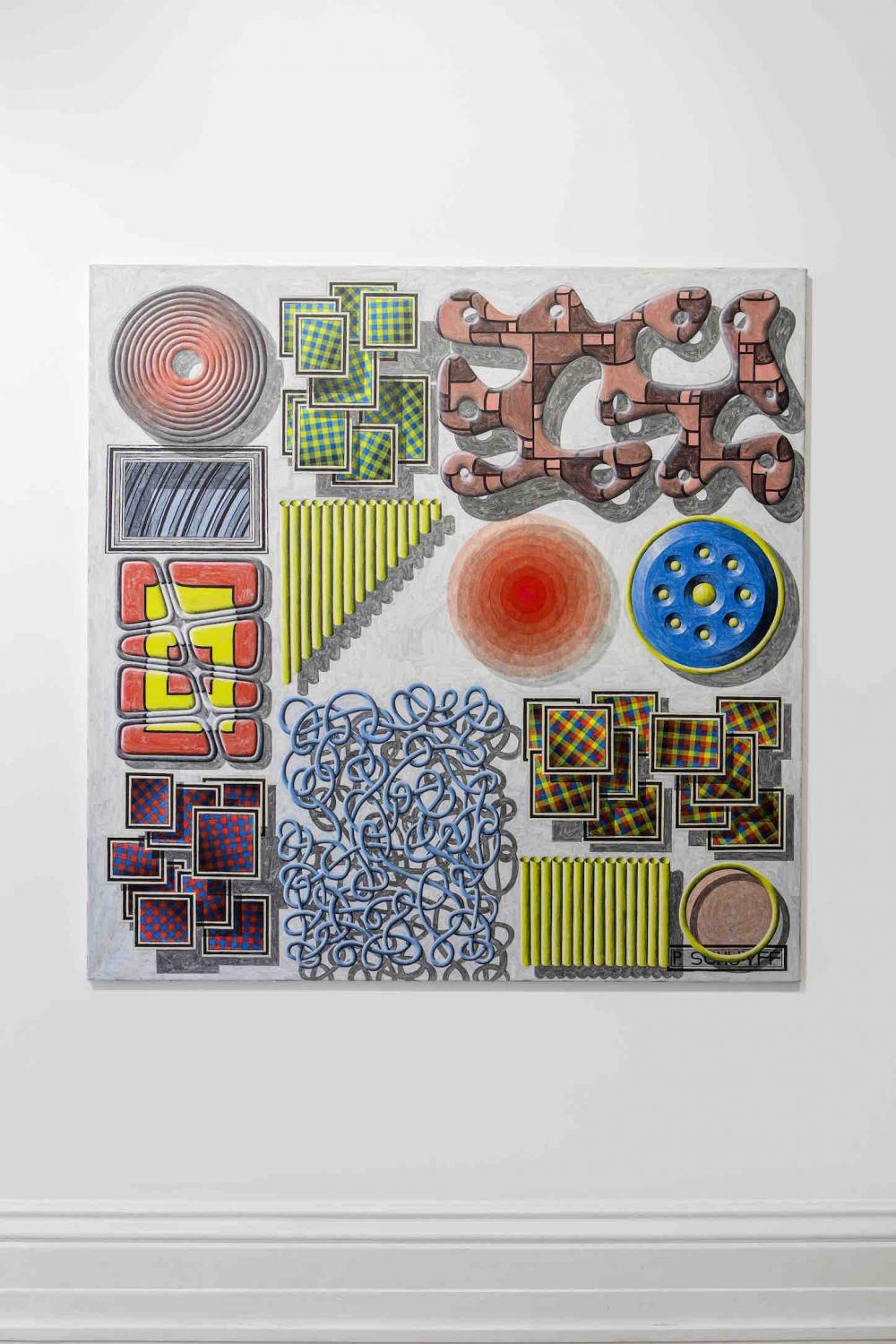

Peter: I’ve been working on these samplers. It’s what I often do when I get kinda frustrated, or right after a big show. I sit down and make these very obsessive renderings that are like a smorgasbord, a sampler, of all my ouvres.

Nick: Like the one you had in your show at Carl Kostyál’s a few years back?

Peter: Yes, that one was called ‘Plato Combinato’. That’s a really good example of these samplers. I’m making a few of those. I needed these pencil leads for one where I’m kinda making a portrait of the show that I have at White Cube.

Nick: Why do you think you tend to do these sampler works after completing shows. Are you visually cataloguing or processing the shows?

Peter: Yeah, I’m visually cataloguing the show I guess, just so I can see it clearly. I’ve always had a fascination with pictures of pictures, whether it’s in 17th Dutch paintings where you often see paintings hanging in the background or in those preposterous 18th century paintings of salons. I’ve often commissioned friends and colleagues to make drawings or paintings of my drawings and paintings. They help me see my own work a little bit clearer.

Nick: What do you like about pictures of pictures?

Peter: Do you know what a Claude Glass is? It’s a piece of black glass, like a mirror, and artists, mostly the Impressionists I believe, would use them to look at their paintings. It renders your painting in black and white and that gives you some distance. Like the abstract expressionists would, y’know, squint at their paintings to see them more clearly or look at them upside down. I love looking at my paintings on an iPhone, especially in my studio, I have a really dark studio so if I photograph it on the iPhone that’s the first time I see it in any kind of light, y’know? And, yeah, it gives you some distance and perspective.

Nick: I managed to catch your show just before I left London and it’s stunning, so; congratulations… but commiserations on the timing. It opened just as this crisis started unfolding in London. How are you feeling about it all?

Peter: It hurts, of course. I’ve been looking forward to this for a couple of years now and I guess I was expecting the show to be a liminal moment for me, y’know? With a before and after. Somehow that before and after thing has been taken away a bit. But if it would have been a show of new paintings, I think would have really been demolished. I would have felt just horrible.

Nick: Because of all the labour you would have invested in the work?

Peter: No, no, it’s not the invested labour, it’s very much about momentum. When I show new paintings, they’re very much paintings I want to show now, not later. Do you know what I mean? Whereas these painting were shown last year, and many people know them already, so it just doesn’t feel quite as much of a loss.

Nick: …They were shown in your exhibition ‘Has Been’ that was on at Le Consortium and at the Kunsthalle Fribourg…

Peter: Yeah. The show at White Cube is obviously more finely tuned, a more specific body of work. At Le Consortium and at Fri Art there were a lot of… I call them ‘figurative’ paintings, these shapes that I would paint. But at White Cube it’s only non-objective work.

Nick: What’s it like walking into a show of works of yours from three to almost four decades ago? Do you still feel connected to the paintings?

Peter: I’m really impressed by them! I’m impressed that, y’know, I was young, and handsome, [Laughs] and so I could afford not to give a shit, which is a great recipe for making paintings! Today I’m old and cynical so I have another way of not giving a shit, which enables me to make really clean and clear paintings and I love that. There was a lot of time in between where I kinda couldn’t do that. When I see these works, especially when I saw them at Le Consortium, I was surprised with how big they are and how much balls I had, my God! Especially the paintings at White Cube, y’know, the audacity I had…. there’s nothing, there’s like nothing there, y’know!

Nick: We’ve talked over the years and you’ve always said your paintings are ‘about nothing’. Is that how you talked and thought about the paintings when you were making them back in the ‘80’s?

Peter: Yeah, I did. A teacher of mine in Vancouver, Michael Morris, used to talk about the problem of nothing. I guess it was almost a spiritual principle of work not needing to be about something. I think when I got to New York that came more naturally. I definitely always talked about it [in this way]. It’s always been an issue. When I showed in Germany in the mid-80’s, I remember a lot of the German artists just being mystified with how little was there in the work, y’know! [Laughs]. There was not a whole lot going on there. Which is sweet, if you have the comfort to do it. Those paintings in the White Cube show are from a moment where I was very comfortable, cos I was young and I was indestructible. That definitely helped and it was nothing for me to get out the way.

Nick: Just before I called you I was talking to a friend of mine, Darren Flook, who runs Freehouse gallery in East London. He’s just started representing Meyer Vaisman…

Peter: Oh wonderful, I love Meyer!

Nick: Yes, we just acquired one of Meyer’s tapestry works for the collection.

Peter: Excellent, excellent buy!

Nick: Thank you! Anyway we were talking about the ‘Neo-Geo’ label you’re both pinned to. Was the Neo Geo thing made up afterwards by critics, or the market, or whoever? Or was there some kind of communality between you, Meyer Vaisman, Peter Halley, Philip Taaffe, Bickerton, Koons…

Peter: I guess there were things that we all had in common, that might have been interesting for certain critics and curators to write and think about. And there were a few colleagues, like Peter Halley, or Phillip Taaffe, whose work I have a real formal relationship with, but I don’t think that really has anything to do with it… But I should say that I didn’t actually hang out with most of those people and I very rarely talked art with them. It was definitely was not a scene… But calling us Neo-Geo, that’s doing of curators and critics…

Nick: Darren made the interesting point that the Neo-Geo labelling feels like the last time that there was some kind of collective attempt from the art world to package a group of artists together into a movement. After that it really does become the soup of commercial, post-modernity… with plenty artists floating around but no chunky movements.

Peter: That’s very interesting, and I think he’s right! I remember that all of a sudden people were talking about pluralism a lot after that ’80’s period… But I wasn’t really paying attention. That being said, for that reason also, the Neo Geo label seemed convenient but useless to me. It was convenient because there were people doing projects and stuff [around these idea of Neo Geo], and I was always happy to say ‘yeah, sure, I’ll do that.’ Any formal notions about my work are so irreverent anyway. Whatever units my paintings are broken into, geometrically, is kind of arbitrary. I have a reasonable eye—it’s not a brilliant one—but it’s not something I worry about like Mondrian would have, or in a very different way Sol LeWitt would have done. For Sol it was a still a consideration. For me it’s never been a consideration at all.

Nick: What are your considerations when you’re making a work?

[Long pause]

Peter: Wow, that’s a hard one to answer. Well, as few as possible! There’s really very few. I’ve been working for years to whittle it down, so there’s really very few, cos at the end of the day that’s where I make my best work.

Nick: Is it about minimising thought?

Peter: Yes, it’s about getting out of the way, listening to what the paintings wanna do… paintings plural… listening to where they want to go. I guess that’s something that I leant from music, when I started making music in my late Forties. I realised that the most important thing when you make music is to know how to listen, otherwise it’s just a fucking mess, or an ego-trip, or whatever. So it is with the paintings. I mean it’s not perfect, but I’ve gotten better at listening. There’s a lot of buttons, a lot of dials you have to turn way down in order to be able to listen.

Nick: Looking at your recent work it looks like there hasn’t been a huge amount of change in your practice since the 80’s. Is that fair? Does change matter to you?

Peter: That’s fair. I mean, it’s definitely fair to say if you’re quantifying the work. I think it comes from a very different direction now. Because, like I said before, when I was young it was easy to get out of the way because I was young, and now it’s easier for me to get out of the way because I’m older. Before I didn’t know any better, now I do, and the result is some fluidity in the studio.

Nick: Could you talk me through the process of making one of the geometric paintings something like ‘Blackjack’.

Peter: It’s very easy, Nick, it’s just exactly what it looks like! I mean, there are some paintings that I make that are kind of magic tricks, and I probably wouldn’t give away the trick! [Laughs] But ‘Blackjack’ for example, even if somebody doesn’t paint, they can look at it and see how it was made!

Nick: In the collection we have some of your 80s watercolours, which I love…

Peter: Great. What I’m working on now is sort of an accounting of those works. Because I’m using watercolour and paper I’ve been thinking about those.

Nick: I’ve been trying to get my head around how you achieve the precise gradations of colour and shade in them…

Peter: So, I’ll answer it this way. That great big painting downstairs at White Cube, the one with the prism of colours, it’s a ten-foot-square canvas, and it’s broken up into one-inch units, and I made that with a four-inch brush with a round bristle. So knowing that, you should be able to figure out how I made them… It’s the same with those watercolours. Those watercolours were broken up into little squares that are about a half a centimetre squared or something? There’s no way I’m going to pay attention to each of those little squares.

Nick: Well, it’s a very effective trick then, because the apparent precision is amazing in those works.

Peter: …And just like a good magic show it’s all about engineering.

Nick: I was also trying to figure out in what order you did things in the watercolours… whether the pencil grids or the actual painting came first…

Peter: What’s funny is that while I was starting this thing today, I was asking myself exactly the same question, and I couldn’t remember! [Laughs]

Modern Forms

Nick: This is obviously a huge show at White Cube. You have gone through up’s and down’s in your career and you work had been getting a lot of attention again, recently. How does that feel?

Peter: The attention fuels me because I guess I make my work for other people, it’s not my own investigation really. Like, if I were stuck on a deserted island, would I make art? I’m not sure I would fucking bother, y’know! My work really needs to be pointed outwards, otherwise it kinda doesn’t happen really.

/

Peter Schuyff was born in Baarn, Netherlands in 1958.

In 2017, Fri Art, Kunsthalle Fribourg, Switzerland, and Le Consortium, Dijon, France, both presented ‘Has Been’, a retrospective of Schuyff’s work made between 1981 and 1989.

His public exhibitions include the Whitney Biennial, New York (2014); New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York (2005); and The Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Ridgefield, US (1996).

His work can be found in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and The Fisher Landau Foundation, New York.

He currently lives and works in the Netherlands.

Further info on Peter’s current shows (sadly under lockdown):

Peter Schuyff, White Cube, curated by Katharine Kostyal

Peter Schuyff, Works on Paper, Carl Kostyál

Peter is represented by:

Also…

Meyer Vaisman at Freehouse54