Last year, at Paradise Row, Billy Fraser (b. 1995, Bath) and Simone Mudde (b. 1989, Oud-Beijerland) showed together for the first time, in an exhibition presenting paired galleries and artists, aimed at exemplifying the ecologies that exist across London’s contemporary art scene. Despite the disparity of their wider practices, the work they showed here demonstrated a shared interest in interrogating colour and form, combining tones in novel formations to affect new languages and reactions. Since then, the artists have been engaging in a dialogue around the intersection at which their practices meet, spending time in each other’s studios in order to experiment and develop material around this. The project has culminated in a duo exhibition at Sherbet Green, London, titled Opticks, which runs until 29 July 2023.

For Modern Forms, Fraser and Mudde sat down with Mazzy-Mae Green to discuss durational experimentation, colour and perception.

Mazzy-Mae Green: In many ways, your practices are incredibly different. Where do you see them intersecting?

Simone Mudde: Definitely a penchant for specific materials, and deconstructing colour.

Billy Fraser: What I’m making in a 3D realm, Simone is making in an analogue, 2D realm, and that’s how I consider our practices. I have colour in different weights and densities, and she has flat colour in different depths and distances. This is the first time I’ve been paired with someone that really resonates with the work I’m making so formally, and that’s been really exciting for me.

SM: The first time we met in your studio and you showed me your methodologies and tests and cubes, I saw so many similarities in how we experiment with colour, and how we’re both trying to create a language within our materials.

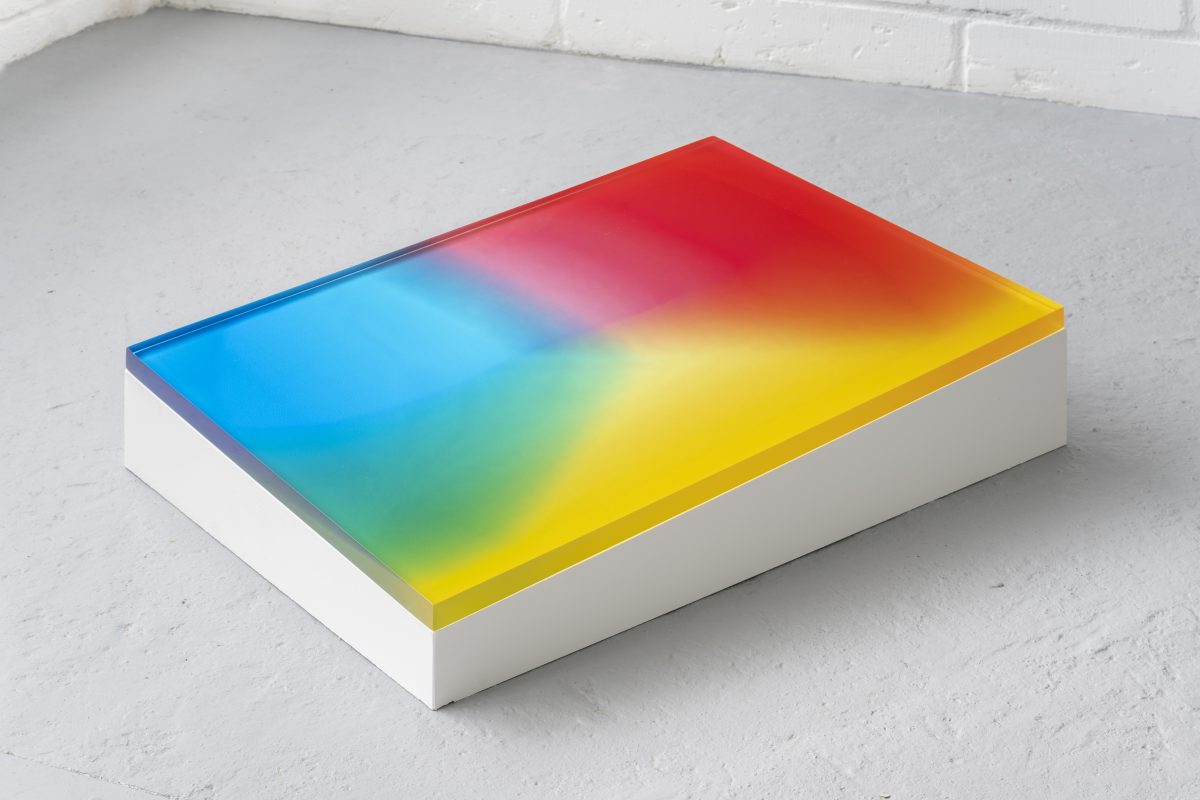

BF: We’re delivering something that’s visually similar, through ways of working and processes that are completely different. What we’re left with, when caught at the right angle, are two different works that could be mistaken for being the same work. It’s only when you view them from an angle that you see the Colourscapes as sculptural works. Before that, they both exist in 2D.

MG: When we were working on the show, we talked about how experiments in colour and form are integral across art history. How do you get to that point where you begin experimenting in these organised ways?

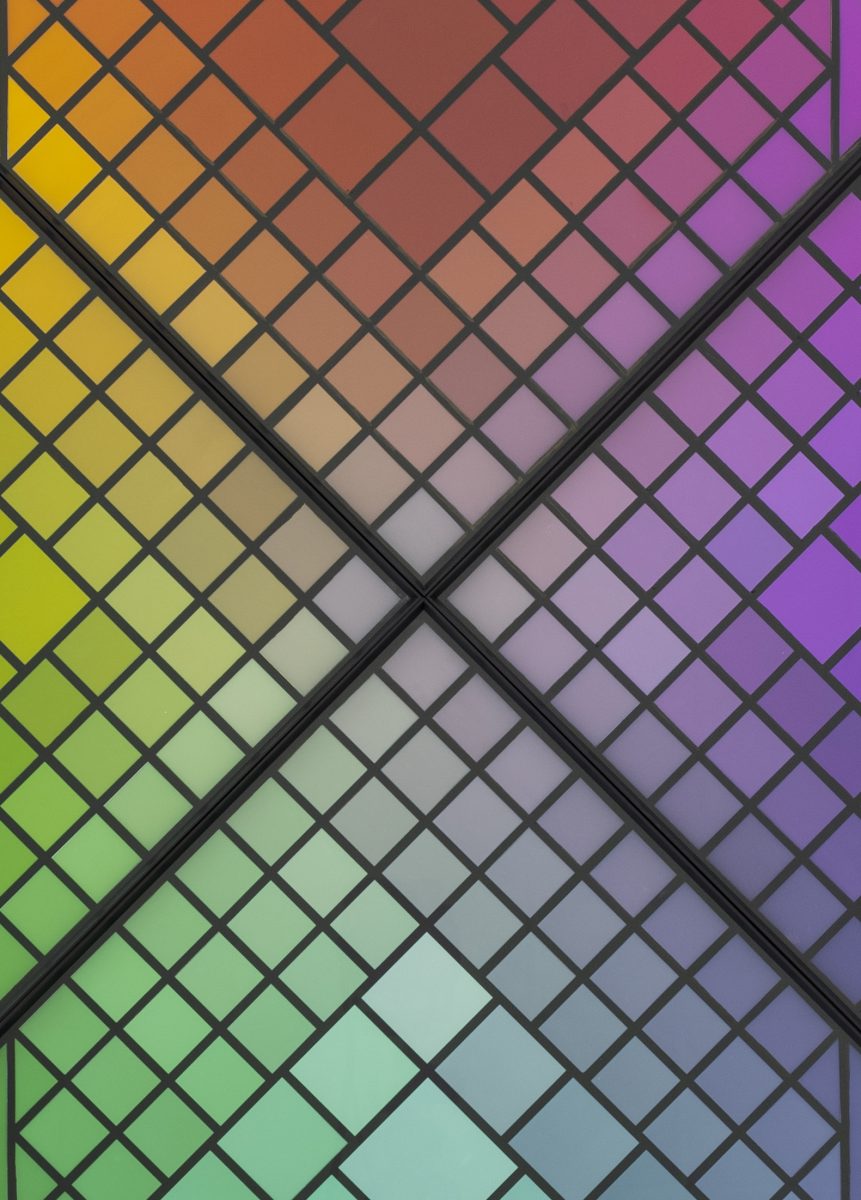

SM: For me, it was a byproduct, because I was making these works called Folds, where I would fold photographic darkroom paper into tessellation folds, and I would use the enlarger to light these sculptures using different coloured light. So then only the shadows of the sculptures are imprinted in colour, and in order to make that, I would do a lot of tests, making small stencils where I would flip little squares to create that colour green that I really like, or a certain orange that I love. And just through doing all these tests, suddenly my walls would fill up with all these colour charts. I slowly became really fond of these colour charts, and it became part of the work. So the colour charts were originally a means for making other work, but later became a leading part of the work. I was also naturally interested in making something systematic, I think that’s in my character. I make systems for myself, so I’d create these objects where I can make multiple colours on one sheet and I can get information about the difference in colours and steps, and even me designing those little sheets, suddenly every choice I made, like how big, or how these little things correlate to each other, became a conscious step into making, and slowly that started to take over.

MG: Yours is quite different, Billy, right? I remember you saying that you’d started working with these materials, and then stripped it back to experimenting.

BF: These are as simple an enquiry into polyester resin that I could approach. The first work I made with resin was an incredibly complicated depiction of the Apollo 11 moon landing, widely considered mankind’s greatest industrial achievement, as an analogy for the industrial sublime. We managed to get a whole load of metal up to the moon, and three astronauts waltzed around and did the unthinkable. After this sculpture, I kept moving to simpler and simpler ground. Resin is such a complex material, I wanted to quantify the working methodologies of the medium. These Colourscapes are data; a way to understand colour within a medium, and it’s incredibly rewarding. Each work informs the next. Everything I make exists so that I can learn from it.

MG: I really love this about your practices, the fact that you position them as evolving bodies. In terms of the idea of visualising colour, what does that mean in your work?

SM: I’m trying to control the colours, to become the ultimate master of the darkroom, and that quest has led me to trying to make a colour space. Colour is a visual language. For example, if we talk about existing colour spaces, such as RGB or CMYK, it’s something that needs to be translated, which is a process inherent to language. When thinking of colour in the same way as language, I love that these spaces become an explanation of colour as a visual object. They show one universe, one object, one scope. They are trying to show the possibilities and combinations but also the limits of photographic colours. Beside the famous digital colour spaces there are also a lot of colour systems made for painting that I find very inspiring. They come in crazy shapes and beautiful objects.

MG: Thinking about painting within this, Billy, you originally came from a painting discipline. You’ve before referenced these works as part of an expanded painting practice, but it got me thinking about what it means that they’re not paintings, and whether there’s almost a removal of the artist’s hand? Is there something in the durational aspect of what you’re doing that returns that closeness?

BF: That was really fun for me to think about. I love painting. Before I could spell painting, I was painting. For me, no one gets to decide what or what isn’t a painting. I wrote my dissertation about Barnett Newman claiming that the sublime was now, now then being Abstract Expressionism, and I just totally rejected the idea that painting could touch the sublime, if the sublime is taken in its literal all-encompassing meaning. So I wanted to tread further than a painted canvas. That’s when I made the industrial analogy as a way of self containing an idea within a world of resin, as opposed to it being a flat painted surface. So, for me, I am still a painter.

MG: I think about it differently somehow. For me, the language of painting, the association we have with it, is that it can contain elements of wonder. It already carries that association because of Abstract Expressionism or symbolism, or other historical movements rooted in the evocation of emotion, and that association almost conditions our understanding of painting as something that can induce that visceral reaction, and perhaps that also helps it do so. Painting has always had its own specific position, and power. Take photography, for example. Photography has never held the prestige of painting. I’m not making a statement about whether I agree with that, but there is something about how we position painting in society that we don’t do for other mediums. The idea of exploring a parallel relationship between humans and another medium is interesting.

BF: I think that merely speaks of the rich history of painting. They’re both alien objects, but one has a 3000-year discourse around it, and the other was invented 200 years ago. I think my love of painting comes from that historical canon, but it can be so rigid in its classification. These things I’m making aren’t really paintings, they’re objects, yet they are 4.5 cm wide, and they are in the traditional 3:4 ratio, so they take up space in the same way a canvas does. I think there’s a resistance to expansion; painting is what it is, it has to have a canvas and paint, and – at the moment – it’s not considered an object. You see contemporary artists who glue attachments or string LEDs to their paintings, there’s a strange transition between painting and object. I’m very happy to move into the world of an object, yet still occupy the same space as a painting. What really excites me is the technology of painting. What will painting be in 200 years? And interesting, too, is that resin isn’t a hugely expansive medium. Contemporary examples would be Anish Kapoor, who makes massive resin sculptures, or Sterling Ruby, who coats things in resin. We’re at the very beginning of resin as sculpture, so there are only a few dozen people in my field that are my contemporaries, as opposed to thousands upon thousands with painting.

MG: You’re also working with a medium associated with distance, Simone – photographs – yet you spend a day in the darkroom constructing each panel, and you’re so close to the work, which is different to how I associate the modern photographic process, and again I feel that intimacy reinserted between you and the work through your process.

SM: We all walk around with a camera in our pockets, we all have a phone. Everyone has access to photographs, and everyone shares photographs, but I almost see that as a separate thing to my practice. The type of photography I’m researching in my work is actually the really technical, really old school kind of photography, and I’m always looking for ways to pull apart the medium to separate things and insert something new, or use something old to create something new. And it’s that systematic thinking, and an interest in machines, that underpins what I do. And the more knowledge I acquire on how the darkroom works, the more I see and feel its limitations, so I’m always trying to hack the darkroom, integrating new processes and tricks into it. All the knowledge I have of darkroom printing has come from experimentation. It’s very complicated and I spend a lot of time in the dark, but it’s also very simple. There’s a lamp and a lens and paper, and something in between, or sometimes there’s not even something in between. There’s so much variety within the tiny adjustments you can make within these confines.

MG: That mimics scientific experiments in other fields, too.

BF: Having a control variable, yeah! My process is so similar. These are all very specific experiments. The first set, which we showed together at Paradise Row, fed into the works presented at Sherbet Green today.

MG: And what and who influences you in the work?

BF: I read a book called The American Technological Sublime by David E. Nye, and I think my biggest influence to date has been the idea that the sublime experience is ever involving and ever growing. Primitive man saw Niagara Falls and felt beholden to it, and then when the steam train came around, and a huge hunk of metal flew through the landscape at 80 mph, you looked at Niagara Falls and you thought, that’s just bloody water and… Anyway, that experience evolves as we evolve. We have the internet and we have mass data, all of a sudden that same steam train is old news. When we made the nuclear bomb, we transcended the notion of sublime experience. No longer were we beholden to the world, the world is beholden to us, we are capable of destroying it. This complex of us succeeding the sublime experience by making something so definitive that we can bring an end to the world, that has been the largest underlying figment of my art practice today. Everything sits within this trajectory. For me, it’s about notions of the sublime, notions of an impending apocalypse, past present future, the beginning and the end.

MG: Something that strikes me in your practice is that you’re pulling, often, on similar threads explored by the YBAs, which isn’t an influence I feel heavily across the London contemporary mood.

BF: I’m definitely heavily influenced by them. It’s funny, a friend, Florence Sweeney, said something to me recently that I really resonated with. She said: “I wish I was a YBA artist, and I could have a whole studio full of shit, and a gallerist would come once a year, take out one of these pieces of shit, and that would be the artwork. I wouldn’t have to worry about what time of day to post or being shadow banned for my expression. We’re unconsciously saturating ourselves into the ether, scared to be opinionated incase of upsetting gallerists, collectors, influencer patrons… it goes against the punk ethos of what it is to be an artist. The cost of living doesn’t help contemporary artists, in the days of the YBAs they could set up shop for next for nothing and get their art out in the world, that’s the difference.”

If you look at Damien Hirst or Tracey Emin, every few years their practices reinvent themselves, and for better or worse, I have a lot of respect for that. It’s exciting, and it’s what artists are for me: inventors.

MG: That notion of shifting cycles was also one of the defining aspects of modernism. Movements that were constantly changing. And it wasn’t different artists for different movements. One artist might have been involved in five movements, constantly innovating and shifting to try and represent modernity.

BF: So are we like… post movements now?

MG: We’re probably just in a super late stage of capitalism where a product is a product, and art has for so long carried that tension between being a product and not, because it’s also totally not a product, and I believe it’s a human impulse to create. What about you, Simone?

SM: I don’t have as big an answer as Billy…

BF: Sorry, we’re two beers in and I got excited.

SM: I think it’s a combination of many different aspects for me. I look at different artists all the time. I think a lot of inspiration comes from discovering something technically, like unlocking a new level in photography, and I think people that inspire me are always people that are obsessed with making work and doing their thing. In photography, I’ve always been really into Stephen Gill. One of his series, titled The Pillar, is set on the farm where he lives, which has one pillar, and he installed a camera and recorded everything happening around that pillar. They’re incredibly simple, but really effective, and I love how you dive into his obsession when you see one of his projects. I also really like Tauba Auerbach, which is more painting related, but she also meanders beautifully between different mediums, and has this amazing RGB book which is a beautiful object, but her practice is also paintings made from fabrics, and her work can vary a lot. And then recently I saw Helen Frankenthaler at Dulwich Picture Gallery. So beautiful. The colour schemes really inspire me, and remind me to follow intuition in the use of colour and material.

MG: How do you feel that this body of work and your experiments relate to your wider work and what you’ll show at the end of this month [July] at your first solo exhibition, taking place at Lismore Castle?

SM: It’s different work, but the two bodies heavily inform one another. At Lismore, I will show a couple of colour separation works. It’s a technique I’ve used before, where I use black and white images to create a colour image through filtration. And in this show, I also have some images where I use objects as negatives. So there are loads of photograms made using this technique. The show is almost a collaboration between this beautiful garden at Lismore and my darkroom. It’s still incredibly technical, but it has a different subject and application. Like the photograms that Billy and I made for Opticks. I always have a lot of negatives in my hands. I’m actually always looking at negative photos. I’m always looking at things that are translucent and colourful to see how I can use them as negatives. Beautiful photograms can be made from interesting objects, like these small experiments from Billy, these translucent sample cubes. There’s just so much going on, and if you hold them against the light, you can see that there’s so many layers of colour, and from the moment I saw them in the studio, I knew we needed to see how we could print them.